Britain’s economy may be the only one that contracts in 2023 according to the IMF’s latest quarterly assessment, dealing a blow to hopes that a recession can be avoided. The pound was the second worst performing currency after the yen last year amid an energy crisis, political chaos and a botched budget, which all added to the existing post-Brexit and post-pandemic challenges. But how accurate are the IMF’s forecasts when no other major economy is expected to shrink, and can the pound shrug off the gloom to keep its uptrend intact?

Tumbling down the growth league table

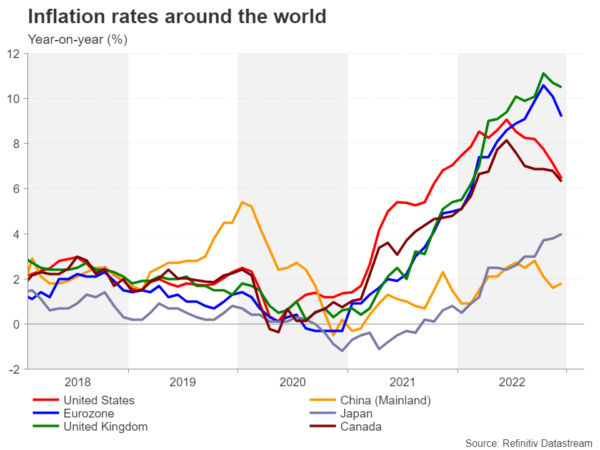

It’s been a fairly solid start to the year so far for sterling and the economic indicators haven’t been as bad as the negative headlines would suggest. In fact, the United Kingdom likely grew the fastest among the G7 in 2022 as the economy continued to recover from the deep pandemic slump of 2020. But it’s safe to say that the reopening boost has now well and truly faded, and Britain may now have a bigger inflation problem on its hands than other countries.

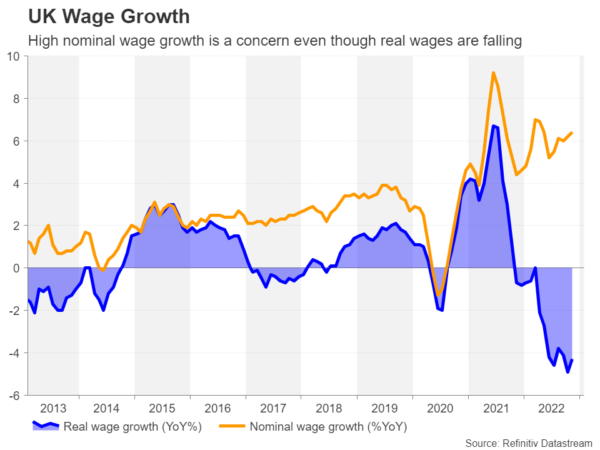

Brexit has made the price of certain goods costlier after the UK left the single market, however, the bigger impact has been on the labour market. Worker shortages have been evident after freedom of movement with the rest of the EU came to an end following Brexit, adding to wage pressures. The pandemic exacerbated this problem as many people left the workforce, mainly due to early retirement or being unable to work because of long-term health effects from Covid.

Inflation not falling fast enough

This goes some way in explaining why inflation in the UK peaked higher and has climbed down less than it has in the euro area or in the United States despite the significant decline in energy prices. Wages across the UK are currently rising at an annual pace of more than 6%. Whilst that’s not high enough to turn real wage growth positive, it does add to the cost burden for businesses, who in turn have to put up their prices. In addition, the way the UK energy market is structured compared to Europe has contributed to gas and electricity bills surging far more for British households than on the continent.

The persistently strong inflationary pressures forced the Bank of England to accelerate its rate hikes in the autumn, increasing the risk of overtightening and thereby choking off growth even more. Although the same can be said for the ECB, the signs on inflation are a little more encouraging in the euro area. Plus, the downside risks are somewhat less pronounced for Eurozone economies.

Post-Brexit blues?

Whatever dangers lie ahead in 2023, for example, should the Ukraine conflict escalate and there is an energy crisis part two, Europe will have China’s reopening to fall back on. The comparative boost to UK exporters will probably be less significant from any rebound in Chinese demand. But there are other pressing issues facing Britain.

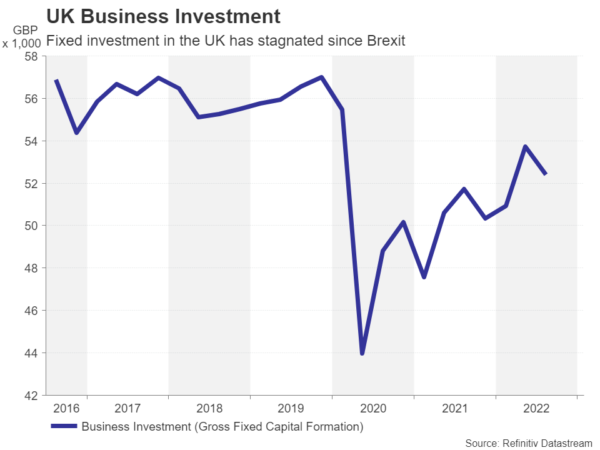

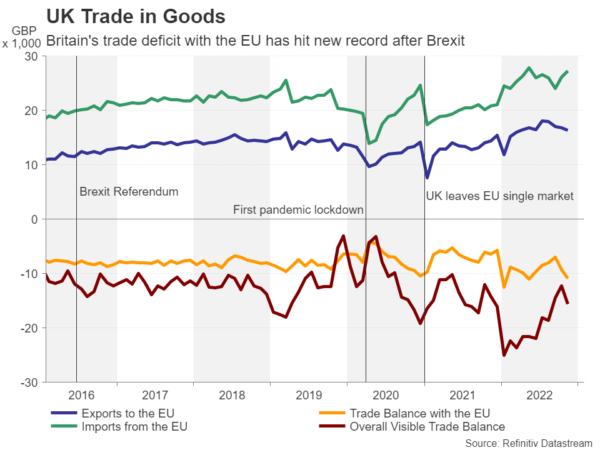

Business investment stopped growing after Brexit and then collapsed after the first Covid lockdown. Not only has investment yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels, but Britain was investing less heading into the virus crisis. Another aftereffect of Brexit has been on trade. After leaving the EU single market in its entirety on January 1, 2021, exports as well as imports briefly plummeted. Although both have now risen above pre-pandemic levels, imports have jumped more than exports, leaving the trade deficit with the EU near all-time highs.

Britain’s total trade deficit has at least now started to improve after hitting a new record at the beginning of 2022 and the current account deficit as a percent of GDP has also been narrowing in the last few years, which bodes well for sterling. Still, it is hard for investors to get too excited about the UK economy following the events of the summer and autumn.

Unprecedented political turmoil

Three prime ministers in two months is not something that’s usually synonymous with the UK, while the budget episode in September may have permanently damaged investor confidence in the economy. Yet, even though Liz Truss’ short time as PM brought havoc to the markets, she was right about one thing: the UK needs a growth plan.

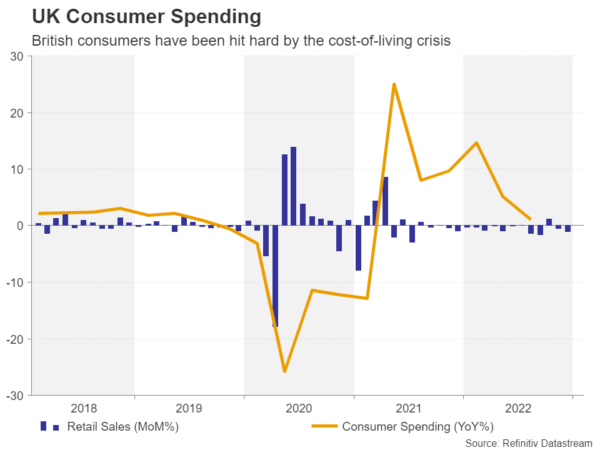

Truss also managed to secure more support to help families through the energy crisis. Without it, households would likely be spending a lot less right now. Consumers are the main growth engine of the UK economy and despite all the government assistance, the outlook remains quite bleak, primarily because borrowing costs are going up, which means higher mortgages for homeowners.

Consumers’ woes set to worsen in 2023

Add to that the possibility that it might take longer for inflation to come down substantially in the UK, 2023 could be an even worse year for UK consumers. The government, meanwhile, is also tightening its purse strings as it needs to reign in spending after borrowing ballooned during the pandemic. This is positive from the inflation perspective as it should help dampen price pressures, but there will be no extra cash to go around for tax cuts or other growth initiatives.

However, a potentially bigger concern for businesses as well as investors is the lack of a long-term economic strategy by the Conservative party. Rishi Sunak replacing Truss may have restored political calm and eased the market panic, but his premiership has so far been marred by endless strikes in the public sector and a series of Tory sleaze allegations.

Can new leadership fix Britain’s problems?

The IMF may therefore have a point in being so much more pessimistic about Britain’s growth prospects as the economy is facing multiple headwinds. Even if the severity of some of these challenges has been overdone and the UK fares better than anticipated this year, investors’ outlook is unlikely to change until there is a new government in Downing Street that has a clear vision for the country.

At this point, the markets’ best bet of that might just be the Labour party. Under the current leader, Keir Starmer, the party has shifted closer towards Tony Blair’s New Labour and away from Jeremy Corbyn’s left-wing influences. Thus, a Labour government does not seem like such a big threat anymore and could provide better stability. However, the next general election is not expected until the end of 2024 and it could be difficult for the pound’s outlook to turn dramatically more bullish until then.

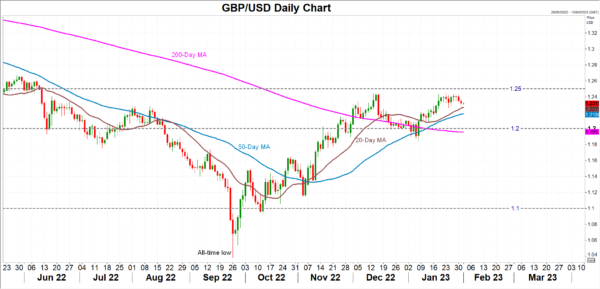

Still some hope for pound bulls

In the meantime, the divergence of monetary policies between the Fed and Bank of England works in sterling’s favour, even if the UK economy underperforms. Nevertheless, a break above $1.25 is critical to sustain the pound’s uptrend.

The big risk, though, is what would happen if the Fed continued to tighten beyond the summer and the Bank of England paused well before that. Sterling could slip back below $1.20 in such a scenario and possibly revisit the $1.10 level as well.