Summary

- The FOMC raised its target range for the fed funds rate by 25 bps at its March 15-16 meeting. However, the minutes of the meeting revealed that some members would have supported a 50 bps rate hike had the conflict in Ukraine, which began only three weeks earlier, not clouded the outlook.

- We look for the FOMC to announce a 50 bps rate hike at the conclusion of its May 3-4 meeting. A parade of Fed speakers have signaled over the past few weeks that they would be comfortable hiking the funds rate by 50 bps at that meeting.

- In our view, the risk that the Committee surprises the market with a 75 bps rate hike, although not our base case call, is materially greater than a 25 bps surprise increase.

- We expect that the FOMC will hike rates by another 50 bps at its June 14-15 meeting before beginning to raise rates at a more gradual 25 bps-per-meeting pace in July.

- We also look for the FOMC to announce a plan at its May 3-4 meeting to start shrinking its balance sheet by no longer reinvesting the principal payments received from its securities holdings, up to a monthly cap.

- Specifically, we expect the initial monthly caps to be $40 billion for Treasury securities and $25 billion for mortgage-backed securities (MBS), with the caps eventually rising to $60B and $35B per month, respectively. We expect runoff will start in June and the monthly caps to be fully phased in by August.

- In our view, the first 50 bps rate hike in over 20 years and the start of balance sheet runoff shows that the Federal Reserve means business in its fight against inflation.

Tepid Start to Tightening to Shift Into a Higher Gear

Efforts by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to embark on its most aggressive tightening campaign in decades got off to a slow start at its March 15-16 meeting. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine just three weeks before the meeting ushered in an added element of uncertainty to the outlook for inflation and growth. With conditions evolving so quickly, the FOMC opted for the more cautious option of a 25 bps increase in the fed funds rate instead of a 50 bps hike. The minutes of the Committee’s meeting in March subsequently revealed that were it not for the near-term uncertainty caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, more participants would have been in agreement with St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, who was the lone dissenter at the meeting, to raise the target range for the fed funds rate by 50 bps.

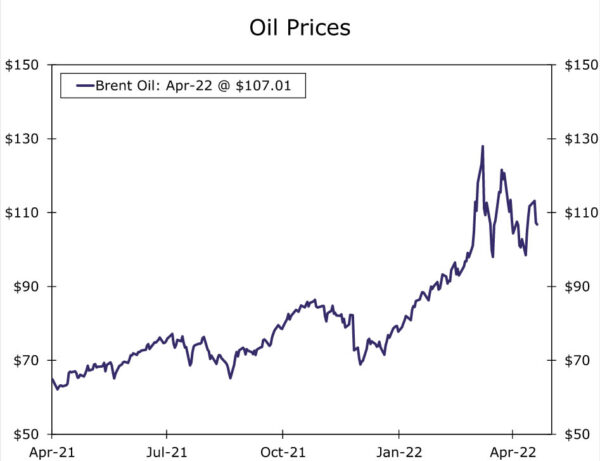

Although a resolution to the conflict in Ukraine is unlikely to come any time soon, initial adjustments from businesses, governments and markets have been made. The worst-case scenarios for energy prices have been avoided thus far. Oil prices have swung widely over the past two months, but have yet to revisit the levels of early March (Figure 1). The limited market reaction, at least thus far, should assuage fears about the severity of the near-term hit to economic growth stemming from sharply higher commodity prices, which supported the case for a more cautious liftoff in March.

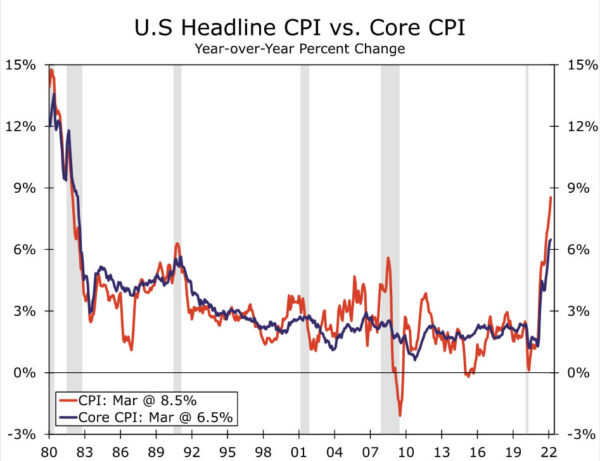

However, the inflation picture still leaves plenty of heartburn for the Committee. The Consumer Price Index in March posted its largest monthly gain since 2005, sending the year-over-year surge to a fresh 40-year high of 8.5% (Figure 2). A modicum of good news came from a softer-than-expected rise in the core index, but even excluding food and energy, prices rose at a 3.9% annualized pace—still well above the Fed’s target. March may be the high watermark for this cycle, but inflation’s strong momentum suggests it will not be easy to rein in. With the rate of PCE inflation currently about three-fold the central bank’s target, the FOMC still has significant work to do to alleviate price pressures.

It is not only inflation data that suggest an already over-heated economy got even hotter since the last FOMC meeting in mid-March. The labor market has continued to tighten rapidly, even with some long-awaited improvement on the supply front. Job growth surpassed expectations in March after factoring in another hefty round of upward revisions. Moreover, the unemployment rate fell to 3.6%, just a tick above its pre-COVID low as well as the median estimate that the FOMC made in March of where the rate will end this year.

Making Up for Lost Time: The 50 Bps Hike Is Back

It is no wonder then that Fed officials are in a greater hurry to remove accommodation. We expect the FOMC will make up for lost time in March and raise the fed funds rate by 50 bps at its May 3-4 meeting. Over the past few weeks, a parade of Fed speakers have signaled that they would be comfortable hiking the funds rate 50 bps at a single meeting, rather than what has become the customary 25 bps. Support for a larger move runs the gamut of key leaders such as Chair Powell, Governor Brainard and FOMC Vice Chair Williams as well as doves such as Charles Evans, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and Mary Daly, president of the San Francisco Fed. With the minutes of the March meeting having reinforced broad willingness to move 50 bps at one or more upcoming meetings, markets are fully priced for a 50 bps hike at the May 3-4 meeting.

Could the FOMC surprise markets with something other than a 50 bps increase? We see the chance of a hawkish, 75 bps hike as low but materially greater than the chance of the Fed underwhelming with a 25 bps increase. A 25 bps rise would come out of left field, in our view, given further strength in inflation and the labor market data and the steady patter of Fed speak in recent weeks hinting at a bigger move. A 75 bps hike seems to be the greater risk to our call given that the Committee is clearly on edge about the current state of inflation and is eager to get policy to a more neutral setting. St. Louis President James Bullard, who has been out front on the increasingly hawkish mindset of the Committee, stated a 75 bps hike should not be ruled out. That said, he also noted that it is not his base case at present.

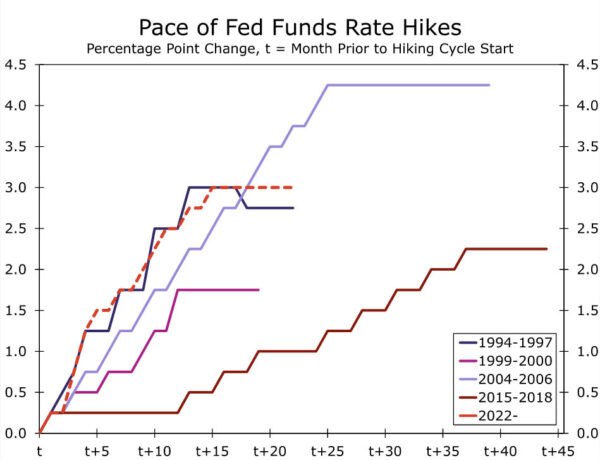

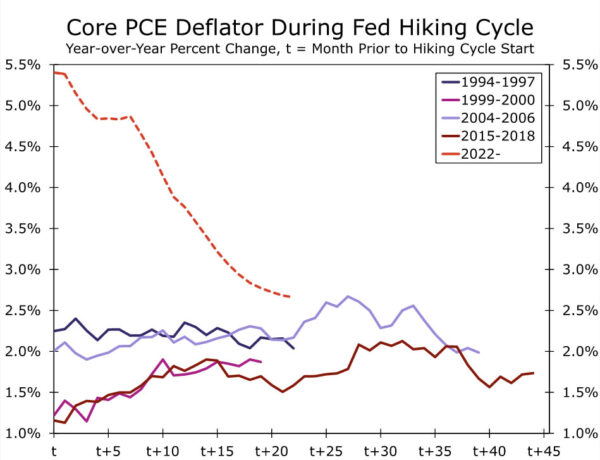

Rather than deliver a 75 bps hike at the May meeting, we expect to see the FOMC expedite tightening by following up May’s 50 bps increase with another 50 bps hike at the June 14-15 meeting before beginning to raise rates at a more gradual 25 bps-per-meeting pace in July. This would put the Fed on a similarly steep path as the 1994 tightening cycle (Figure 3), although a lower natural rate of interest today is likely to make the climb ahead more potent. Yet inflation so wide of the Fed’s target and the accommodative starting point of policy today leads us to believe the FOMC will opt for such a strong antidote (Figure 4).

The May meeting will not include an updated Summary of Economic Projections, so the statement that will be released at the end of the meeting and Chair Powell’s press conference will take on greater importance in signaling how quickly the Committee is preparing to tighten policy, and potentially how far. If the FOMC places greater emphasis on reducing inflation in its statement, perhaps by noting low inflation is imperative to achieving the employment portion of its mandate over the longer term, we would view this as a sign the Committee continues to move in an increasingly hawkish direction.

Not Just 50: Fed Balance Sheet Runoff a Second Form of Tightening

Like the expected path of the fed funds rate, the outlook for the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has shifted significantly in recent months. In early January we laid out the case for the Federal Reserve to start reducing the size of its balance sheet beginning in October. Since then, the FOMC has pivoted even more sharply in a hawkish direction, and as a result we have steadily pulled forward our expected start date for balance sheet reductions. It now appears the time is upon us. In addition to lifting the fed funds rate, we look for the FOMC to announce a plan at its May 3-4 meeting to start shrinking its balance sheet by no longer reinvesting the principal payments received from its securities holdings, up to a monthly cap. We expect the initial monthly caps to be $40 billion for Treasury securities and $25 billion for mortgage-backed securities (MBS), with the caps eventually rising to $60B and $35B per month, respectively. More specifically, we expect runoff to start in June and for the monthly caps to be fully phased in by August.

The actual details that we expect will be announced on May 4 could obviously differ from our expectations. For example, the phase-in of the monthly caps could be a month or two longer than the three month phase-in we currently expect, or the initial caps could be a bit different from $40B/$25B. However, the terminal caps of $60B and $35B come directly from the March 15-16 FOMC minutes in which it was revealed that “participants generally agreed” that caps of this amount would likely be appropriate. Thus, deviations from the terminal caps of $60 billion and $35 billion would be a surprise.

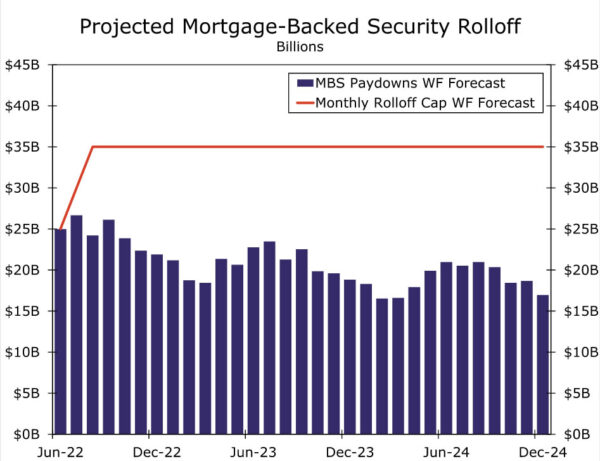

It is important to remember that these monthly caps operate as a ceiling on monthly asset redemptions and not a floor. For MBS, it does not appear the caps will be binding anytime soon. Projected MBS paydowns over the next couple of years are roughly $15B-$25B per month, well below the anticipated $35B billion cap (Figure 5). Outright MBS sales to make up the difference are possible, but the March FOMC minutes signaled that MBS sales would not be considered until balance sheet runoff was “well under way.”

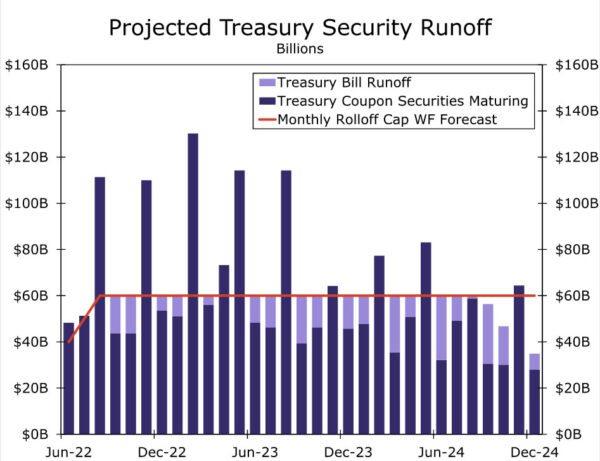

The monthly cap plays a bigger role in Treasury security redemptions. In some months, the amount of maturing Treasury notes and bonds (i.e. coupon-bearing securities) that the Federal Reserve owns exceed the cap. For example, in August about $111 billion coupon-bearing Treasury securities will mature on the Fed’s balance sheet, but only $60 billion would be redeemed because of the monthly cap (Figure 6). However, in September the Federal Reserve will have only $43 billion worth of maturing coupon-bearing Treasury securities. The March FOMC minutes signaled that the Federal Reserve would redeem Treasury bills in months when Treasury coupon principal payments are below the cap. Under this approach, the redemption of Treasury bills would typically bring the total amount of Treasury redemptions up to the monthly cap. Projected T-bill redemptions are represented by the lavender bars in Figure 6. The Fed owns $326 billion of T-bills, which account for a small share of the central bank’s $5.8 trillion Treasury security holdings. These T-bill holdings are unrelated to monetary policy accommodation and were accumulated between September 2019 and February 2020 to calm Treasury repo markets.

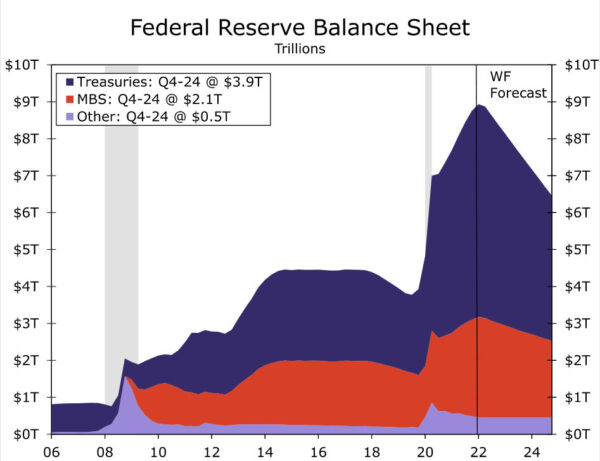

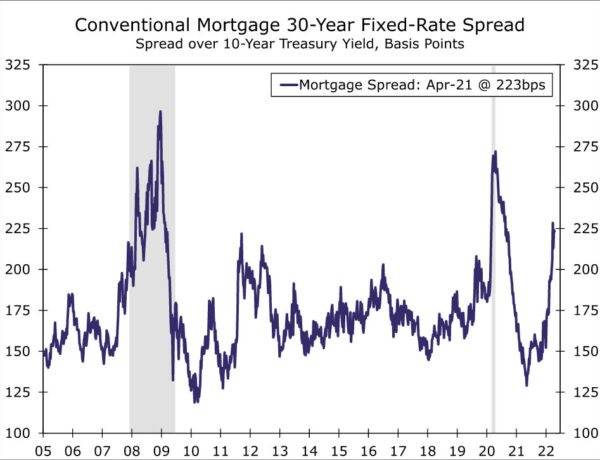

If our assumptions for the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet plan are correct, and if no outright asset sales are executed over the next few years, then the central bank’s balance sheet would shrink from about $9 trillion today to roughly $6.5 trillion at the end of 2024 (Figure 7). Balance sheet runoff will serve as a secondary, passive form of monetary policy tightening in addition to the primary tightening tool: increases in the target range for the federal funds rate. Financial markets have responded to this anticipated change in policy. Intermediate- and longer-term yields on Treasury securities are higher and mortgage spreads are wider in recent months (Figure 8). We suspect most of the impact on yields from balance sheet runoff already has been priced in by financial markets, as we discussed in a recent special report. That said, we doubt the impact has been fully priced, and the overall effect from balance sheet runoff is highly uncertain, a fact Chair Powell acknowledged in his most recent press conference.

Regardless of the exact magnitude, the May 3-4 FOMC meeting likely will send a clear signal from monetary policymakers. The first 50 bps rate hike in over 20 years and the start of balance sheet runoff shows that the Federal Reserve means business in its fight against inflation.