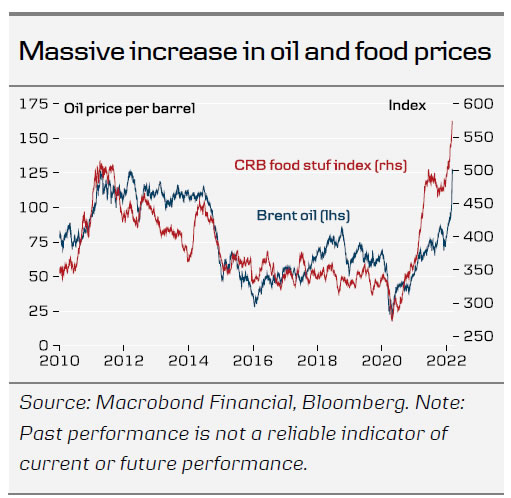

The war in Ukraine has added a big supply shock to a global economy where supply had not yet fully recovered from the previous supply shock related to the pandemic. On top of reduced labour force that contributed to widespread labour shortage, the world is now facing a reduction in the supply of another important input factor to production: commodities. With much of Russian and Ukrainian supply taken out of the equation in oil markets, many metal markets and grain markets, the world is facing a further shortage. Any companies having production in or sourcing components from Russia or Ukraine will also face new supply disruptions.

The result is clear: Inflation is moving even higher as we see with sharp increases in commodity prices. There is only one cure to it in the short term. As long as supply is reduced, demand has to come down. Otherwise there will continue to be too much demand relative to supply. That may very well require a recession in demand – and thus in the whole economy.

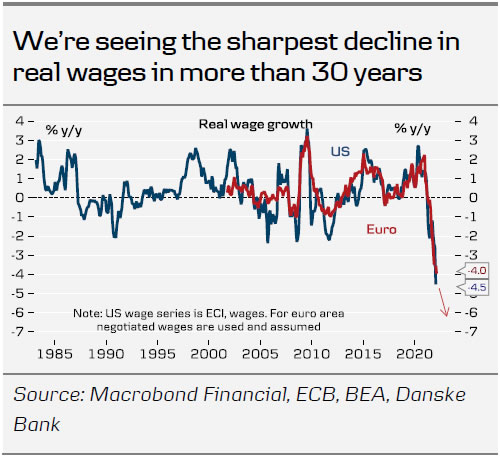

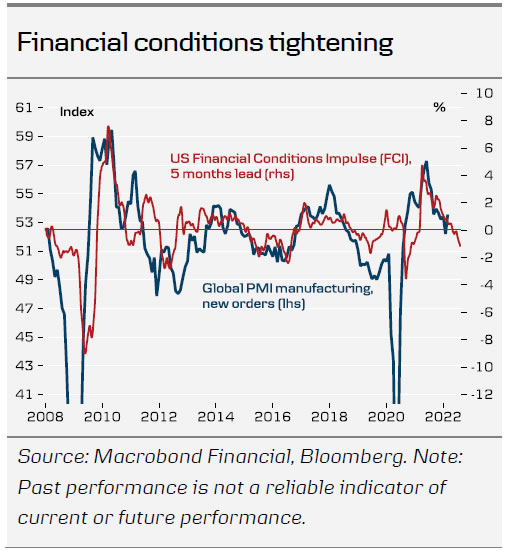

Some of the decline in demand will likely happen by itself. Businesses could put some planned investments on hold due to renewed uncertainty over the outlook. Significant financial tightening is taking place with credit spreads wider and equities sharply lower. Consumer demand is also taking a hit from eroded purchasing power due to the rise in inflation as not least energy and food prices move higher. In the short term, euro inflation could go up to 8-9%, which with would shave up to 6% off real wages. A similar situation is evident in the US. We are witnessing the biggest decline in real wages in more than 30 years. The rise is food prices is creating a global food crisis, which will have dire effects in many emerging markets and developing countries, many of which have still not yet recovered from the pandemic.

In order to reduce demand further to stem inflation pressures, central banks are also on course to tighten policy. The Fed has signalled a lift-off next week and more rate hikes are lined up for the rest of this year. We also expect ECB to raise rates in December, although it has become a closer call. The demand slowdown from the above mentioned factors may do the job for the ECB.

The bottom line is, we currently have significant headwinds to global growth that has increased the risk of recession significantly, especially in Europe. And it could be the case that a recession in demand is in fact needed to be more in line with a global supply that has been reduced and caused new shortages in key production inputs resulting in renewed sharp inflationary pressures. If we do indeed go into recession, we would expect it to be fairly short, as a public driven capex boom within energy sectors, both in oil and green investments, will underpin demand. This would also raise global oil supply in the medium term and energy prices could come down sharply again. China should recover on a 1-year horizon and we also see potential for pent-up demand among European consumers that could come back when the shock abates. The outlook is extremely blurred, though, and any projections have to be taken with a lot of caution. A lot depends on how the war in Ukraine unfolds, how far US and EU goes in terms of energy embargos, government action to mitigate the hit from higher commodity prices, how commodity prices respond and how businesses and consumers react to all this. We are (again) unchartered territory and the crystal ball has suddenly again become very foggy. Over the coming week we will outline some scenarios for where we see the world economy and financial markets evolving based on a different set of assumptions for how the war develops and commodity markets develop. Stay tuned.