Part III: Central Bank Digital Currencies

Summary

- Paper money is a risk-free asset for an individual or business that holds it and a liability of the central bank that issues it. Paper money works well as a medium of exchange for small value payments that are made “in person,” but it does not work as well for payments that are large in value or need to be made remotely.

- Many central banks are contemplating the issuance of their own digital currencies. Similar to paper money, these so-called central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) would be a liability of the central bank and a risk-free asset of the public. Large value payments and remote payment could be made easily with CBDCs, and payments would clear essentially instantaneously.

- But there are complex design issues associated with CBDCs. Bank deposits, which are the liabilities of private sector commercial banks, constitute the vast majority of the money supply of most economies. A CBDC could compete with bank deposits, which could lead to disintermediation from the banking system, especially in times of financial stress. Disintermediation could have devastating consequences for economic growth.

- The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) recently issued the Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP) on a limited basis, making it the first major central bank to launch a digital currency. The DCEP is a liability of the PBoC, but the public acquires it from commercial banks, not directly from the central bank. The DCEP does not pay interest, which should limit the potential disintermediation effects of the digital currency in the Chinese banking system.

- Advanced economies are lagging behind in terms of CBDC issuance. Work on a CBDC in Sweden, which increasingly has become a “cashless” economy, has been underway for more than four years. The Swedish central bank completed a test of an e-krona last year, but no decision has been reached yet about whether to actually issue a CBDC in Sweden. The European Central Bank expects to have a prototype of a digital euro ready for testing sometime in 2023.

- The Federal Reserve recently published a report that lists some basic principles regarding the potential issuance of a U.S. CBDC. But the Fed essentially kicked the decision about the creation of a digital currency back to the executive branch and Congress.

NOT A DEPOSIT. NOT PROTECTED BY SIPC. NOT FDIC INSURED. NOT GUARANTEED. MAY LOSE VALUE. NOT INSURED BY ANY FEDERAL GOVERNMENTAL AGENCY

This commentary is provided for information purposes only and does not contain any recommendations or investment advice. The Firm makes no recommendation as to the suitability of investing in digital assets, including cryptocurrencies. Investments in digital assets carry significant risks, including the possible loss of the principal amount invested. It is only for individuals with a high risk tolerance who can withstand the volatility of the digital asset market. Investors should obtain advice from their own tax, financial, legal and other advisors, and only make investment decisions on the basis of the investor’s own objectives, experience and resources.

Central Banks Are Getting in on the Digital Act

In Part I of this series, we discussed some benefits and drawbacks of digital currencies. One of the notable drawbacks of some cryptocurrencies is their extreme price volatility. For example, daily swings in excess of 10% in the price of Bitcoin are not uncommon, which raises questions about its use as a store of value over short periods of time. There is a category of digital currencies, which are known as stablecoins, that tend to have stable values. But as we discussed in more detail in Part II, a drawback to stablecoins is that they are liabilities of private issuers. They function well normally, but they can be susceptible to “runs” when the public turns risk averse and begins to question the financial viability of the issuer(s).

But there clearly are some desirable characteristics of digital currencies. For starters, digitization allows payments to be made essentially instantaneously, whereas it can take days for checks to “clear.” Additionally, individuals without bank accounts (the “unbanked”) can easily make payments with digital currencies as long as they have a mobile phone. It is for these reasons that central banks, which play a vital role in the traditional payment systems of most economies, have shown a keen interest in potentially developing their own digital currencies. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) defines central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) as “a form of digital money, denominated in the national unit of account, which is a direct liability of the central bank.”1

Parts of the payment systems of most economies are already digitized. For example, commercial banks in the United States have accounts at the Federal Reserve, and the Fed digitally clears trillions of dollars of payments every day for these banks. Moreover, the process of clearing payments is speeding up. The Target2 system of the European Central Bank, which provides real-time gross settlement on most days of the year for banks and other central banks, has been operational since 2007. The Federal Reserve plans to implement its FedNow Service, which will provide real-time clearing on a 24/7 basis, beginning next year.

Essentially all central banks issue their own form of paper money that can be used as a medium of exchange. Paper money is a risk-free asset for an individual or business that holds it and a liability of the central bank that issues it. However, most economies do not yet have a digitized form of their national currency that individuals and businesses can use to make payments. So many central banks are currently focused on the development of “retail” digital currencies. But there are complex design issues underlying the creation of CBDCs, and ill-design could have negative consequences for the banking system in many economies. We will begin by discussing some benefits and drawbacks of CBDCs before turning to a discussion of the work that is underway at some of the world’s major central banks regarding potential issuance of digital currencies.

Potential Benefits of CBDCs

Let’s start with the potential benefits. Paper money (e.g., U.S. dollar bills) serves well as a medium of exchange for small value payments that are made “in person.” For example, using dollar bills to buy a few items at a convenience store is routine. But paper money does not work as well for large value payments and for payments that need to be made remotely. An individual probably would not want to carry $70,000 in cash to a car dealership to buy an expensive new car, nor would he or she want to send cash through the mail to pay for an item, regardless of the price of that item.

A CBDC would be a superior way relative to paper money for individuals to make payments. Similar to paper bills, a CBDC would be a liability of a central bank. But digitization would make it much easier to use a CBDC rather than paper bills because the former would be accessible via a mobile phone. An individual could easily make large payments as well as remote payments with a CBDC. Furthermore, these payments would settle essentially instantaneously; no more waiting for “the check to clear.” This would be especially important for international transactions, which can often be time-consuming and expensive. The World Bank estimates that the cost of sending a $200 payment to another country currently averages nearly $13 in the G-20 economies. CBDCs could potentially be available to “unbanked” individuals as well.2

Additionally, CBDCs could solve some privacy issues that arise with stablecoins, which we briefly discussed in Part II. Private sector issuers of stablecoins have data on the payments that individuals who use their tokens make. Although numerous privately-issued stablecoins exist today, “network effects” could lead to a winnowing process in which only a few stablecoins survive. For example, the BIS notes that 94% of mobile payments in China today are made by just two big tech firms.3 Is it good public policy to have significant amounts of personal data concentrated in the hands of just a few private companies? Of course, a CBDC could give government authorities access to private data, depending on how it is designed.

CBDCs could also offer some benefits to central banks in terms of monetary policy options. Central banks presently are constrained in their ability to take interest rates into negative territory, which may be warranted when economic conditions weaken significantly. Some major central banks (e.g., the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan) have implemented negative interest rates, but these policies apply only to the interest that central banks pay on the reserves that commercial banks hold at the central bank. (Under negative interest rates, commercial banks pay interest to the central bank.) But most commercial banks are hesitant to pass these negative rates on to their depositors and creditors. Consequently, negative interest rates at present do not have much stimulative effect on aggregate demand.

But a CBDC could give a central bank the ability to directly reduce the digital assets of a household or a business by the appropriate interest rate. Faced with the prospect of “paying” the central bank, household and businesses may opt to spend some of their CBDC holdings, thereby giving a boost to aggregate demand. Alternatively, a central bank could stimulate aggregate demand with “helicopter money,” by which the monetary authorities could credit the digital balances of household and businesses.4

Some Notable Drawbacks of CBDCs

But there are also some clear drawbacks to CDBCs. Let’s return to the example above in which an individual wants to buy an expensive new car. In the current payment environment, that person could pay for the car by writing a check, which is a liability of a commercial bank. But before transferring ownership of the car, the car dealer probably would want to verify that the funds are “in the bank” or wait until the check “clears.” Both options can be inconvenient and time-consuming.

In a world in which CBDCs existed, the individual could authorize payment to the car dealer using his or her mobile phone and the funds would be transferred instantaneously. In that sense, the CBDC would work like a debit card. But with a debit card, the individual’s assets are a liability of a commercial bank that the bank uses to finance its loans. The existence of a CBDC could potentially induce individuals and businesses to substitute the liability of a commercial bank for the liability of the central bank. That is, a CBDC could potentially lead to disintermediation from the banking system. Loans account for roughly 80% of the credit that is extended to the non-financial private sector (i.e., households and non-financial businesses) in the United States. This proportion is even higher in other economies that do not have well-developed corporate bond markets like the United States. CBDCs could potentially lead to shrinkage in the balance sheets of many commercial banks, which could have devastating consequences for economic growth.

This disintermediation problem could become particularly acute if central banks paid interest on CBDCs. After all, why would an individual want to keep deposits at a commercial bank if they could hold risk-free assets that earn interest at the central bank? Consequently, most central banks may choose to not pay interest on CBDCs. But this disintermediation problem could still persist during period of financial stress if individuals and businesses choose to move their assets from the commercial banking system to the safety of the central bank. Therefore, a cap on the amount of CBDCs that an individual or business could own may be warranted to minimize the potential risk to the commercial banking system.

Furthermore, central banks do not have the resources to handle all the tasks that the commercial banking system undertakes. For example, according to the FDIC, there are approximately 124 million American households with bank accounts, representing roughly 95% of American households.5 The Federal Reserve simply does not have the resources available to onboard and maintain the accounts of millions of American households, a task that currently is being handled by the nation’s 4,800 insured commercial banks. Central banks in most other economies are also ill-equipped to handle these tasks.

Progress on CBDC Issuance in Major Economies

Despite these drawbacks, some central banks have already launched their own digital currencies with many other central banks actively exploring the potential to do so themselves. According to The Atlantic Council, there were nine countries as of December 2021 which had already launched a CBDC, and 69 others in which a pilot program existed or active development or research was ongoing.

China, which began work on a digital currency in 2014, in recent weeks became the tenth country to have issued a CBDC.6 The digital currency of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) is known formerly as Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DCEP). Similar to paper yuan, the DCEP is a liability of PBoC, but the public acquires the digital currency only from commercial banks, not directly from the PBoC.

The DCEP was designed with small transactions in mind. That is, it is not based on blockchain technology, as are some cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, because that technology would make it cumbersome to handle a high volume of small transactions. In that regard, China’s system reportedly can process 300,000 transactions per second. The DCEP does not pay interest, which should limit the incentive of individuals to switch out of bank deposits and into digital yuan. Therefore, any harmful disintermediation effects on the commercial banking system in China should be limited. The PBoC has rolled out the DCEP on a limited basis, at least for now, and it potentially could evolve over time if circumstances warrant.

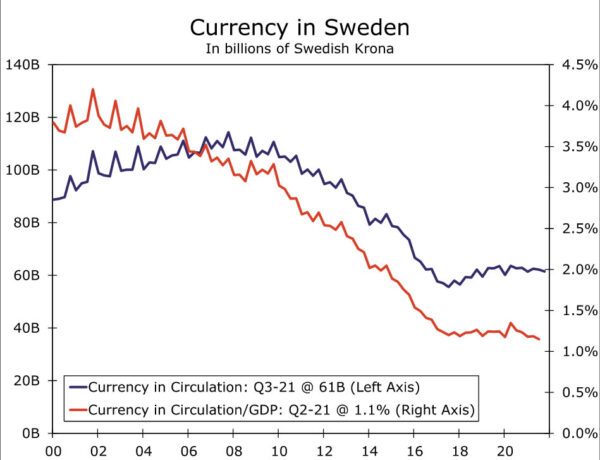

Sweden, where the amount of currency in circulation peaked in 2007, has become an increasingly “cashless” economy. Although the outstanding value of coins and bills has stabilized over the past few years, the amount of currency in circulation relative to the size of the economy is only 1%, a record low (Figure 1). The Swedish Riksbank (the country’s central bank) says on its website that “in response to the increasingly marginalized role of cash, the Riksbank is investigating whether it is possible to issue a digital complement to cash, the e-krona.”

Preliminary work on the design of an “e-krona” began in 2017, which made Sweden one the first central banks among the advanced economies to conduct research on the feasibility of issuing a CBDC, and the central bank completed a test of the e-krona last year. That said, launch of a CBDC in Sweden does not appear imminent, because the central bank continues to state that “at yet no decision has been taken to issue an e-krona.” At the completion of the test, Riksbank Governor Ingves said that Sweden could have CBDC “within five years.”

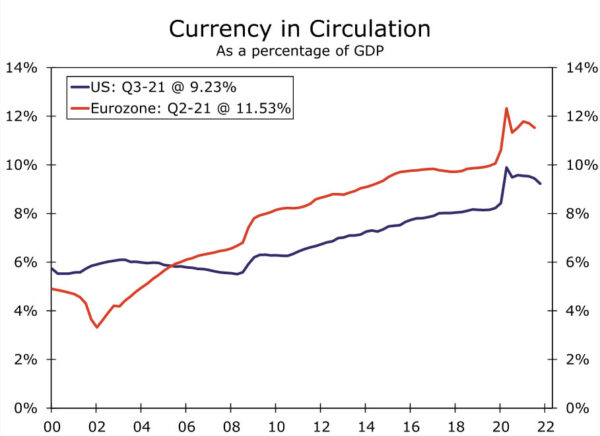

Unlike the circulation of the Swedish krona, which has declined markedly over the past decade or so, the amount of euros in circulation continues to rise, not only in absolute terms but relative to the size of the Eurozone economy as well (Figure 2).7 Nevertheless, the European Central Bank (ECB) established a task force in January 2020 to consider the implication of a digital euro that “could support the Eurosystem’s objectives by providing citizens with access to a safe form of money in the fast-changing digital world.” The ECB published a report on the task force’s findings in October 2020, and it moved to the “investigation phase” of a digital euro in October 2021. According to the ECB’s website, this phase is projected to last 24 months. In testimony to the European Parliament in November, ECB Executive Board Member Panetti said “we expect to narrow down the design-related decisions by the beginning of 2023 and develop a prototype in the following months.” Presumably, it will take more time to test any prototype of a digital currency that the ECB may develop. In short, potential issuance of a digital euro by the ECB appears to be a few years away.

Work on a CBDC for the United State is also underway, and the Federal Reserve recently released a report on its preliminary conclusions. The report does not go into specific design features of a potential digital dollar, but rather highlights some broad principles. Specifically, the report notes that “a potential U.S. CBDC, if one were created, would best serve the needs of the United States by being privacy-protected, intermediated, widely transferable, and identity-verified.”

“Intermediated” means that the Federal Reserve would not issue a digital dollar directly to the public. The digital currency would be a liability of the Fed, but “the private sector would offer accounts or digital wallets to facilitate the management of CBDC holdings and payments.” These holdings would need to be “readily transferable between customers of different intermediaries.” That is, an individual with a CBDC account or wallet at a specific commercial bank should be able to easily send a payment to a person who can then make a deposit in his or her CBDC account or wallet at another commercial bank. Intermediaries would need to verify the identity of their CBDC depositors to protect against money laundering, although “any CBDC would need to strike an appropriate balance between safeguarding the privacy rights of consumers and affording the transparency needed to deter criminal activity.”

The Federal Reserve concluded its report by asking for public comments until May 20, 2022 on the benefits, risks and policy considerations related to a U.S. CBDC. However, the Fed also said that it is not taking a position on the ultimate desirability of a U.S. CBDC, and it kicked the decision back to lawmakers by stating that it “does not intend to proceed with issuance of a CBDC without clear support from the executive branch and from Congress, ideally in the form of specific authorizing law.” But should lawmakers decide to proceed with a CBDC for the United States, some preliminary research on technical issues has already been done, which the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology explain in a recent report.

Conclusion

As we noted in Part I of this series, the dominant form of money that societies have used has evolved over centuries, and there is no inherent reason to believe that its current form (i.e., paper bills and bank deposits) is the last step in the chain of monetary evolution. In that regard, there are some clear benefits to digital currencies that would make their issuance on a “retail” basis attractive to central banks. But the desirability of a CBDC for the public in a specific economy is not entirely clear-cut. There are some complex design issues that require careful considerations, and ill-design of a CBDC could potentially contribute to monetary and financial instability which most central banks strive to avoid.

China recently became the first major country to issue a digital currency for public use, and many other central banks are working to determine whether the potential benefits of a CBDC outweigh the potential costs. Sweden has already tested a prototype CBDC, but the country has not yet determined whether to move forward with actual issuance. The ECB plans to introduce a prototype some time in 2023, but actual issuance of a CBDC in the Eurozone, if it indeed occurs, still looks to be a few years in the future. The Federal Reserve is studying the issue, but it does not intend to proceed with issuance unless specifically authorized to do so by U.S. lawmakers. In short, a world in which CBDCs are circulating widely does not look to be imminent. In the meantime, the digital currency environment will continue to be dominated by private issuers. We will return shortly with some concluding thoughts regarding digital currencies in our fourth and final report in this series.

Endnotes

1 BIS Annual Report 2021, Bank for International Settlements, Basel, SZ, June 2021 (Return)

2 Remittance Prices Worldwide: Issue 38. The World Bank, June 2021. (Return)

3 BIS, op. cit (Return)

4 Milton Friedman first wrote about “helicopter money” in 1969 when he wrote about the effects of a hypothetical helicopter dropping $1000 bills from the sky that were “hastily collected by members of the community.” Ben Bernanke resurrected the term in 2002 when he wrote about potential policies to fight deflation. (Return)

5 “How America Banks: Household Use of Banking and Financial Service” FDIC, 2019. (Return)

6 For further reading on China’s digital currency see Ma, Gene, Conan French and Vanessa Sun, “China Spotlight: The Digital RMB is Still a Form of Cash,” Institute of International Finance, December 2020 and Lowery, Clay, “China’s Digital Currency: National Security Concerns?”, Institute of International Finance, May 2021. (Return)

7 Unlike the Swedish krona, both the euro and the U.S. dollar are used widely outside the Eurozone and the United States, respectively. The Federal Reserve estimates that more than 40% of U.S. dollars are held by foreigners, while the ECB estimates that non-Eurozone residents hold 20% to 25% of outstanding euros. The increase in U.S. dollars and euros in circulation may reflect, at least in part, foreign demand for these major currencies. (Return)