Summary

- The FOMC’s first meeting of the year is likely be a quieter affair than its December meeting, when the Committee accelerated its taper plans and outlined a more aggressive policy path for 2022. There will not be a fresh Summary of Economic Projections, and we expect the FOMC to reaffirm its current pace of tapering, leaving asset purchases on track to end in mid-March.

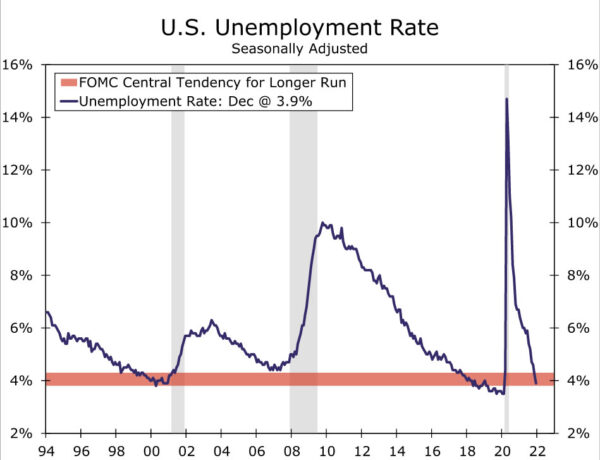

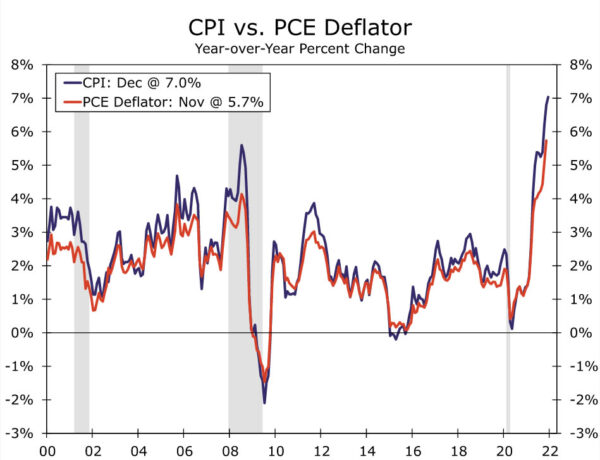

- Although we do not expect any policy changes, there will still be plenty to unpack. Since the FOMC’s December meeting, inflation has gotten further offsides. December’s CPI report showed prices rising 7.0% over the past year, the largest increase in nearly four decades. The labor market also continues to barrel toward “maximum employment”, with the unemployment rate tumbling to 3.9%.

- With the FOMC growing increasingly concerned about inflation, we look for January’s post-meeting statement to signal the fed funds rate could be lifted at its next meeting on March 15-16. Such a hint could come by indicating that the labor market is close to maximum employment, the remaining criteria the Committee has laid out for liftoff. We expect the statement and Chair Powell in his press conference to downplay the temporary slowdown in growth due to the most recent wave of the virus and highlight the overall strength of the labor market.

- Ahead of the blackout period, many FOMC members expressed that they would be comfortable with a raising rates in March. Markets are primed for a hike, pricing in a probability of roughly 90%.

- To stave off a March rate hike, we believe the FOMC would need to see an abrupt slowdown in inflation. Although hiring is likely to stumble in January under the weight of Omicron, the current wave of cases is likely to worsen the existing supply challenges for labor and goods. If inflation continues to surprise to the upside, a March increase will be all but assured. The optics of standing idle with consumer inflation still at 7% will be difficult.

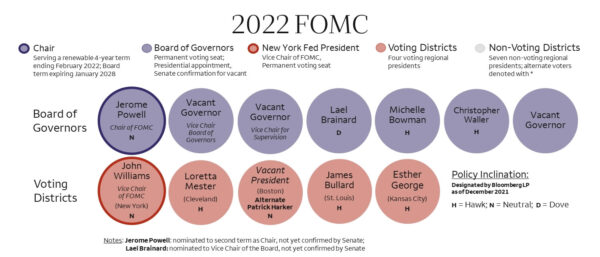

- The January meeting will bring the usual rotation of voting members. On net, this year’s voters lean more hawkish.

- A bigger re-shaping of the Committee this year, however, could come if the three empty Board seats are filled. While it is reasonable to assume the Biden administration’s picks would lean dovish, the highest inflation in a generation may make everyone find their inner-hawk.

- Following a rate increase in March, we look for the FOMC to raise rates 25 bps per quarter through the third quarter of 2023, bringing the fed funds rate to 1.75-2.00%. We also look for the FOMC to announce a reduction in its balance sheet at its September meeting, with runoff beginning in October.

After a Fast Turn, How Quickly Can the Fed Get Policy Up to Speed?

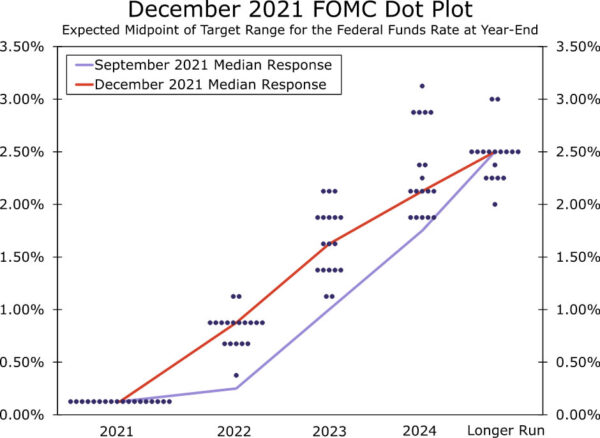

The December FOMC meeting offered yet another illustration of conditions changing at light speed in the pandemic-era economy. After underplaying the risks around inflation for most of the year, the FOMC took a decidedly hawkish turn at its past meeting. The Committee doubled the pace of asset purchase tapering just six weeks after first announcing purchases would start winding down. In addition, it projected that increasing the fed funds rate by 75 bps would be appropriate in 2022 after being evenly split on whether liftoff would be warranted at all this year as recently as September (Figure 1). The pivot went down fairly smoothly with markets, with the accelerated timeline for policy tightening generally perceived as necessary to tackle inflation and avoid an even sharper adjustment later on.

January’s meeting should be more straightforward for Chair Powell, but no less important. The FOMC has made the initial turn onto the road of policy normalization, so now the question becomes its speed. Our expectations for the January meeting is that the FOMC will maintain its current pace of tapering, leaving asset purchases on track to conclude in mid-March, and that it will tee up the fed funds rate to increase as soon as its next meeting on March 15-16.

The Paradox of Omicron: Slower Growth, but Inflation Further Offsides and a Tighter Labor Market

Since the FOMC’s December meeting, COVID cases have once again surged and put GDP growth on weaker footing to start the year. But the Omicron wave also risks inflation getting even further away from the Fed’s goal by exacerbating labor shortages that are already pushing up wages at a rapid clip, and by causing further disruptions to supply chains still struggling to meet exceptionally high demand for goods. December’s data put the FOMC closer to conditions that would warrant tighter policy even before the full impact from Omicron was felt. Despite nonfarm payrolls falling short of expectations, the December employment report showed an ever-tightening labor market. The unemployment rate tumbled to 3.9%, while average hourly earnings surprised to the upside with a 0.6% increase (Figure 2). Inflation also continued to come in strong, with the CPI rising to a 39-year high of 7.0% and the monthly increase in both the headline and core indices coming slightly ahead of consensus expectations (Figure 3).

Gearing Up for March Liftoff

Some analysts have speculated that based on recent data and the FOMC’s increased eagerness to address inflation the Committee will announce an immediate end to bond buying at its January meeting in order to facilitate liftoff at the March 15-16 meeting. Although we expect the FOMC’s increased determination to rein in inflation will lead to a fed funds rate increase at the March meeting, we do not believe the Committee will make any changes to the pace at which it reduces asset purchases at the upcoming meeting. We expect the FOMC to reaffirm it will pare back purchases at a pace of $20 billion per month for Treasury securities and $10 billion per month for mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Accelerating the wrap-up of bond buying again at the January meeting would lead to purchases ending only one month earlier than at the current pace of tapering. It is not something that has been floated among Fed officials in recent comments and therefore would come as a surprise to markets. Moreover, we see no issue with the Fed raising rates the same month asset purchases end, considering the decision to stop purchases would have been communicated prior.

In the minutes to the December meeting, most members judged conditions to begin raising rates “could be met relatively soon.” Since the release of the minutes, a number of FOMC members have indicated they would be open to raising rates as early as March. The list includes more hawkish members like Loretta Mester, Raphael Bostic and James Bullard, but also more neutral members like Thomas Barkin, Patrick Harker and even the dovish Mary Daly. Markets are more or less giving the FOMC the green light to raise rates at the March meeting by currently pricing in a probability of roughly 90% for a 25 bp hike.

Statement Changes Likely to Foreshadow March Rate Increase

There will not be an update to the Summary of Economic Projections at this meeting, so any hints that liftoff is likely to come as early as the March meeting will come down to the statement and Chair Powell’s post-meeting press conference. The statement is likely to address the slowdown in activity amid rising COVID cases, but emphasize the overall strength of the labor market. The December meeting confirmed that the inflation criteria for increasing the fed funds rate—inflation at 2% and on track to stay or moderately exceed 2%—had been met, and that the Committee expected to maintain the current fed funds rate “until labor market conditions reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment.”

With the unemployment rate having since fallen to 3.9% and other indicators such as wage growth, quits and layoffs pointing to an even tighter jobs market, we would not be surprised if this line is scrapped. In its place, the Committee could say something similar to October 2015 when it last foreshadowed an increase in the fed funds rate from the zero lower bound was imminent, such as “In determining whether it will be appropriate to raise the target range at its next meeting, the Committee will assess labor market conditions in light of its maximum employment objective and the deviation in inflation from its price stability goal.”

What Could Give the Fed Pause Between Now and March?

While FOMC members are clearly leaning toward an earlier removal of policy accommodation than was sketched out only a few months ago, conditions continue to change quickly and the outlook continues to be clouded by an unusual degree of uncertainty in this environment. Therefore, an increase in the fed funds rate in March is not a forgone conclusion, even if policymakers appear to be leaning heavily that way. The FOMC will receive two more months of data for both the labor market and inflation, which may swing the FOMC’s decision to either take off in March, or take a breath.

With hawkish momentum firmly underway, we expect it would take a sharp slowdown in inflation over the next two months for the FOMC to feel it could wait slightly longer to start hiking rates without putting its price stability goal in further jeopardy. At the very least, we believe the CPI through February would need to fall back below 7%, which would entail monthly gains slowing sharply to around 15 bps (PCE data will only be available through January by the March meeting). Signs of easing would also likely need to be widespread, and not due to areas such as energy or travel services where prices could easily pick up again when COVID cases subside. Data suggesting more slack in the labor market, such as a faster pickup in labor force participation, a stalling of the unemployment rate and slowdown in wage growth, would also likely need to emerge in conjunction with an abrupt softening in inflation.

Further upside surprises to inflation would likely make a March rate hike essentially a done deal. Our own forecast is for the CPI to tick up to 7.1% in January and remain at that rate in February. The optics of standing pat at the March meeting will be tough enough if the CPI still has a 7-handle, but further upside to surprises to inflation before then could make the FOMC feel like it has no choice but to start lifting interest rates. Both Powell and incoming Vice Chair Lael Brainard made clear at their confirmation hearings last week that tackling current inflation is not only imperative to their price stability goal but also to achieving maximum employment.

Everyone Is a Hawk When Inflation is 7%

The first FOMC meeting of the year brings with it the usual rotation of regional Fed presidents voting on the Committee and speculation about how that might tip the FOMC’s policy decisions. The regional Fed presidents voting this year on net lean more hawkish, in our view. Whereas in 2021 we considered one voting regional president to be a “hawk” and one a “dove”, this year we would classify the rotating voters as three hawks and one centrist (Figure 4). That said, with all regional presidents having a seat at the table and influencing discussions, it is hard to see the rotation of voters tipping the balance of any single policy decision. In other words, as in years past, we do not see the rotation of voters being a difference-maker in the path of policy this year.

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P. and Wells Fargo Economics

The nominations for three open Board seats could have a more impactful change on the Committee’s thinking. The White House has nominated Sarah Bloom Raskin for the Vice Chair of Supervision role. She served on the Board from 2010 to 2014, and her speeches as a Governor tended to focus on regulatory issues. During that time she never dissented, signaling she is not likely to stray from the center of the Committee on monetary policy.

It is reasonable to expect that other picks for the Board would lean dovish given the administration’s emphasis on diversity and inequality and the Fed’s own emphasis on employment as a “broad an inclusive” goal. Economists Lisa Cook and Philip Jefferson have received nominations for the two other Board positions. Cook’s research has focused on inequality, and Jefferson’s has focused on labor markets and poverty, including the benefits of running a “high pressure” economy to support the labor market.

But the benefits of maintaining accommodative monetary policy are harder to justify when inflation is running more than double the Fed’s target and the labor market is by nearly all measures tight. The labor market and inflation dynamics are much different in this expansion compared with the 2010s. We expect the highest inflation in a generation to make hawks of all Committee members this year.

Following an increase in March, we anticipate the FOMC will raise the fed funds rate 25 bps per quarter through Q3-2023, bringing the target range to 1.75-2.00%. We also look for the FOMC to announce a reduction in its balance sheet at its September meeting this year, with runoff beginning the following month.