Summary

- The July 27-28 FOMC meeting is not expected to bring any changes in policy or even major hints on the timing of an eventual change. Without updated economic projections or a fresh “dot plot,” the July meeting will be about word games.

- Since the June meeting, job growth strengthened more than anticipated and inflation continued to come in much hotter. That will keep eyes and ears keenly attuned to signs that the FOMC may pull forward the eventual tapering of asset purchases, a topic it has already confirmed will be on the table.

- We still expect the FOMC to hold off on a formal announcement of tapering until its December 14-15 meeting, with purchases starting to be reduced in January of next year at a pace of $10B per month for Treasury securities and $5B per month for mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

- Market participants generally appear on board with a late 2021 announcement as well, which is key to avoiding another tantrum. Perhaps most importantly, committee members are split in their views, and it will take time to build a consensus.

- Potential catalysts for an earlier taper stem from inflation continuing to surprise to the upside, which might convince Fed officials that recent price pressures will be longer lasting, and a growing discomfort on the part of some officials about MBS purchases at a time when home prices are soaring.

- Less appreciated is the risk that tapering will not be announced until 2022. The case here rests on the fading fiscal support and concerns over COVID due to variants or the duration of vaccine effectiveness, any of which could lead to a sharper slowdown in activity. After years of undershooting its inflation goal and with an appreciation of how a strong labor market can support marginalized workers, the FOMC might err on the side of supporting the labor market and take a slower approach to adjusting policy.

Stay Tuned for Scenes from the Next Episode

Like any good episodic TV series, the June FOMC meeting was comfortably routine and predictable in some ways and yet just interesting enough to hold your attention with developments that were not entirely expected, and critically, it ended on a cliff-hanger.

Even though the upcoming meeting is in July, we are not expecting any fireworks. Without a Summary of Economic Projections and a new dot plot, the only thing to unpack will be the subtle nuances of language. At some point, we expect the FOMC will finally offer clear guidance on when it will begin to taper its pace of asset purchases, but this meeting is not it. In a nutshell, the July FOMC meeting will mostly be about word games. What policymakers say in the carefully crafted statement and what Chair Powell says in the press conference will be seized upon for every possible indication it might offer about the timing of the eventual tapering of asset purchases.

Although it is increasingly evident that inflation is rising more quickly than the Fed expected, most Fed policymakers are looking past the inflation data for now, convinced of their thesis that the nature of surging prices is transitory and determined to draw tight the slack it still sees in the labor market. Our own forecast suggests that inflation is more enduring than what policymakers currently expect, but decisions about tapering will be made on their forecast, not ours. So even though we have our doubts about just how transitory various inflation factors may be, we maintain our call that the FOMC will not formally announce a plan to reduce asset purchases until its December 15 meeting, with tapering kicking off in January.

In this July FOMC preview, we: (1) Recap where we left off with Fed policy in June, (2) cover what has happened over the inter-meeting with respect to employment and inflation, (3) explain our rationale for a formal taper announcement in December and (4) lay out the risks to tapering being announced either earlier or later than our December call.

At some point, we expect the FOMC will finally offer clear guidance on when it will begin to taper its pace of asset purchases, but this meeting is not it.

Concerns Over Inflation Were Rising Before June’s Hot Data

At its June meeting, the FOMC made no policy changes. The fed funds rate was left between 0.00% and 0.25% and the $120B monthly pace of asset purchases was maintained. That was all as expected. The June Summary of Economic Projections, however, brought a notable shift in the dot plot. Of the 18 committee members, seven expected the fed funds rate to be higher at the end of next year, up from four in March, and 11 members penciled in at least two rate hikes by the end of 2023. The expectation for an earlier liftoff for rates was largely a function of the fact that most members raised their inflation forecasts and saw risks to those higher estimates as skewed to the upside.

There were also some technical tweaks, which we had been expecting and had written about in prior versions of this Flashlight publication. Specifically, the FOMC raised the interest rate that the Fed pays to banks on reserves that they hold at the central bank, as well as the rate on the Fed’s reverse repurchase agreement facility. These are technical adjustments that are meant to improve functioning in money markets rather than a signal of imminent monetary tightening.

The cliff-hanger ending came in the press conference. When asked about the eventual timing of tapering asset purchases, Chair Powell said, “You can think of this meeting that we had as the ‘talking about talking about’ meeting, if you like.” In other words, the FOMC got the ball rolling on the process of eventually tapering, and according to the meeting minutes, agreed to continue discussions at “coming meetings.”

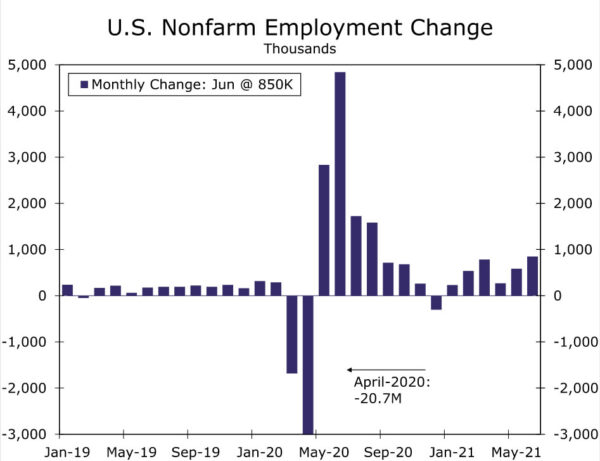

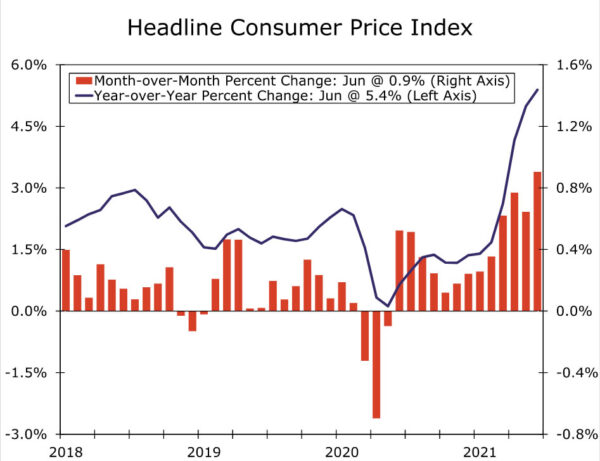

The FOMC has tied its taper timing to when “substantial further progress” is made on the Fed’s employment and price stability goals. Since its previous meeting, we have seen notable headway on both those fronts. Job growth strengthened in June with employment up 850K, the most since last August (Figure 1). Workers are also seeing big pay increases, with average hourly earnings rocketing higher in low-pay industries. Notably, inflation continues to surprise to the upside. The Consumer Price Index rose a scorching 0.9% in June, roughly double estimates, while U.S. producer price inflation also jumped and is up more than 7% over the past year (Figure 2).

Eyeing a December Announcement to Reduce Asset Purchases

Between the FOMC stating discussions are starting on asset purchases and progress on employment and inflation picking up, it seems a tapering announcement is drawing nearer. Yet, we still do not anticipate a formal announcement until the December 15 meeting, where purchases begin to decline in January at a pace of $10B per month for Treasury securities and $5B per month for mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

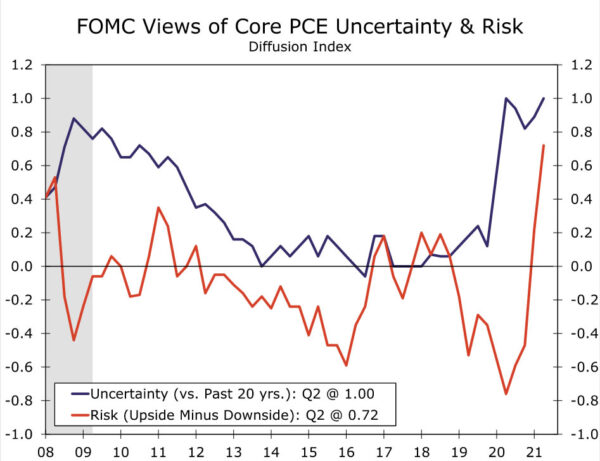

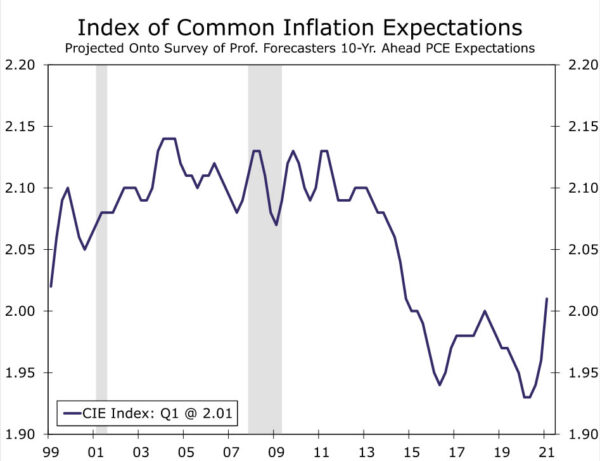

For one, it seems that many FOMC members want a clearer view on how inflation and hiring will unfold beyond the first few months of reopening and amid fading fiscal support. While inflation has come in hotter than expected the past few months, Chair Powell has maintained the view that the spike is temporary. But, uncertainty is historically high, with several FOMC members noting inflation cannot be accurately assessed at this point (Figure 3). The Fed’s outcome-based approach therefore seems to warrant a few more months of data, especially since Fed officials have remarked that inflation expectations remain consistent with inflation running at 2% over the long run (Figure 4).

Similarly, Fed officials appear to want more progress on employment and a clearer view of labor market conditions once factors contributing to current labor shortages have time to fade. According to the June minutes, participants expected conditions to improve “throughout the summer and into the fall.” Yet, we do not expect to get a decent read on how much childcare issues related to remote learning or the expiration of extra unemployment benefits are affecting the labor market until the October jobs report, which be published on November 5, two days after the November FOMC meeting concludes.

More broadly, there appears to be a split within the FOMC between members wanting to see more progress and more information and those thinking conditions will be met earlier than previously thought. Building a consensus will take time.

An announcement at year-end also makes sense from a market perspective. Avoiding a “taper tantrum” like in 2013 is at the forefront of policymakers’ minds. That means getting markets on the same page with regard to timing. Surveys suggest most market participants seem to expect asset purchases to start declining in Q1.1 We suspect the Fed would not risk rocking the boat on that assumption and do not believe it would have enough runway to prepare markets for an earlier kickoff. The December FOMC meeting will include updates to the Summary of Economic Projections and the dot plot, which should also help the Fed communicate its outlook to the market. Continuing asset purchases at their current pace through December would also reduce the risk of any year-end related liquidity issues.

4% Inflation: The Case for Tapering Earlier

An additional reason we have maintained our forecast for a tapering announcement at the December FOMC meeting is that we believe this meeting has the best balance of risks from a timing perspective. Most market participants seem focused on the possibility of a sooner-than-expected taper. In many ways, this makes sense. The Federal Reserve began buying at the current pace of $80 billion of Treasury securities and $40 billion of MBS per month about a year ago. At the time, the U.S. economy was still in dire straits as it emerged from one of the sharpest contractions in output and employment in American history. Fast-forward to today and the U.S. economy is far from a full employment and stable inflation nirvana, but it is clearly no longer on the cusp of collapse either. Accordingly, the case for an emergency setting for monetary policy is much weaker.

If the FOMC announces a taper before December, we suspect it would occur at the November 3 meeting. Anything earlier than this strikes us as unlikely. By the November meeting, our baseline forecast projects the economy will have recovered half of the jobs that were missing when the committee first stated it would need to see “substantial further progress” toward its maximum employment and price stability goals. Our forecast for inflation as measured by the core PCE deflator is 3.7% year over year in Q4-2021, about 70bps above the FOMC’s median projection from the June meeting (Figure 5). If the employment and/or the inflation data are even just a little stronger than we expect over the next few months, one could easily argue the Fed’s criteria has been met to start tapering.

The run up in home prices over the past year could serve as another factor to push the FOMC to start tapering a bit earlier than our baseline forecast (Figure 6). The June FOMC minutes made clear some officials were weary of recent home price gains and suggested scaling back MBS purchases more quickly or earlier than Treasury purchases. We suspect the FOMC would want to avoid the complication of a two-tiered taper, but the discomfort over supporting the housing market could pull forward the kickoff of what we expect to be an evenly paced tapering process between MBS and Treasury purchases.

Not Your Grandfather’s Fed: The Case for a Later Taper

The scenario in which the taper is announced sometime later than the December FOMC meeting is perhaps a bit more difficult to envision during the summer boom of 2021 and recent upside surprises to both job growth and inflation, but we do believe it is a possibility. Even in our above-consensus baseline forecast, at year-end the U.S. economy is still short about 3.5 million jobs compared to the pre-pandemic level of employment, and this rises to roughly 5.5 million when counting the employment gains that likely would have occurred in the absence of the pandemic (Figure 7). On inflation, the recent overshoot of the Fed’s target still pales in comparison to the years of below-target inflation that prevailed for most of the 2010s. Although home prices have skyrocketed, the culprit does not appear to be households over leveraging or banks lending to riskier borrowers. Unlike the mid-2000s, the aggregate household debt-to-income ratio is not on an upward ascent (Figure 8), and in Q1-2021 73% of mortgage origination volume went to borrowers with a credit score of 760 or above, much higher than the average of 24% in 2006.

Thus, if job growth disappoints and/or inflation cools sooners than we anticipate, the FOMC may choose to delay its tapering plans a bit longer in order to ensure the coast is clear. It is not especially hard to imagine the conditions in which growth and inflation disappoint later this year. The fiscal impulse from the two major COVID relief bills passed in December 2020 and March 2021 will have largely faded by the fall, and the snapback to more “normal” economic growth rates could occur much sooner than expected if consumers do not lean on their pile of pandemic-induced savings to sustain robust spending growth.

The public health front also looms as a possible downside risk. New variants and the durability of immunity are still being studied, many workers and children are set to return to offices and schools in the fall and colder weather has been a catalyst for higher case counts as people spend more time indoors. Even if economic growth is still solid on an absolute basis, a notable downshift on a relative basis could give Fed policymakers some pause. Under this scenario, perhaps the FOMC waits a few more months to begin the tapering process. By that time, the economy should be through the worst of any winter-related COVID disruptions, and the additional economic data points will provide more information on the true run rate for economic growth and inflation.

Although this is not our base case, it is a possibility we feel is underappreciated, and it makes us more comfortable with our forecast of a tapering announcement in December. Certainly, the FOMC is concerned about inflation that is well above-target at present. That said, its new framework allows greater leeway on inflation overshooting 2%, while at the same time putting greater emphasis on the need to support the labor market. In addition, the past decade is littered with examples of central banks turning off the spigot too soon only to be disappointed later on by anemic growth and inflation. We suspect many members of the FOMC are just as concerned about repeating these past mistakes as they are with the prospects of overheating, and will err on the side of over-weighting the labor market rather than inflation.

Against this backdrop, we think a projection for a taper announcement at the December FOMC announcement still makes sense, but we acknowledge that conditions could evolve such that the announcement comes a bit earlier or later than that forecast.