Interest rate differentials have traditionally driven the FX market, but now that every major central bank has slashed rates to zero, what will guide currencies? In a nutshell, it might be a blend of how high the risk of future shutdowns is, relative growth performance coming out of the crisis, global risk sentiment, and politics. The defensive yen seems attractive in this brave new world as it no longer suffers from a severe yield disadvantage, while the dollar’s role as a haven may be challenged if second waves of infection hit America.

The lost driver(s)

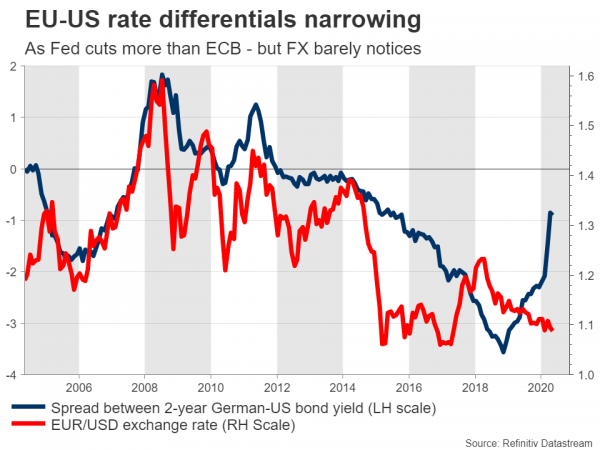

Once upon a time, interest rate differentials between two economies and expectations about how those might change were probably the two most dominant factors behind currency movements. But the world has changed dramatically in 2020, and so has the FX playbook. In the past few months, the major central banks all slashed rates to around zero to protect their economies from an impending recession. Not only have G10 interest rates converged around zero, but the expectations part has mostly died out too: nobody is going to raise rates for a long time.

Of course, minor differences still exist. The Fed now has rates near 0.25% whereas the European Central Bank has them at -0.50%, so assuming similar inflation rates, the dollar still enjoys a small rate advantage. But the key word here is small. The difference is nowhere near as large as it used to be and any future changes will also be minor, diminishing the importance of this theme for currencies. In other words, the days when Fed or ECB rate decisions used to rock the FX market may be long gone.

So what now?

The focus might shift to which nations have handled the health care crisis most effectively. Those economies will be able to re-open with a much lower risk of second waves of infection hitting and therefore a much lower risk of another lockdown. That implies a more durable recovery ahead. The prime examples here are New Zealand and Australia, where new cases are extremely low lately.

On the opposite side of this spectrum, is America. Most states have now partially re-opened, but if someone excludes New York from the nationwide numbers, the outbreak elsewhere has not really reached its peak. That generates a high risk of future shutdowns, raising questions as to how quickly the economy will recover if business activity is disrupted again in the future.

At the end of the day, this all boils down to relative growth performance. Countries that are growing faster coming out of this crisis will likely see their currencies perform the best, and anything that enables that – like additional stimulus packages – will be a positive FX signal.

But mind risk sentiment

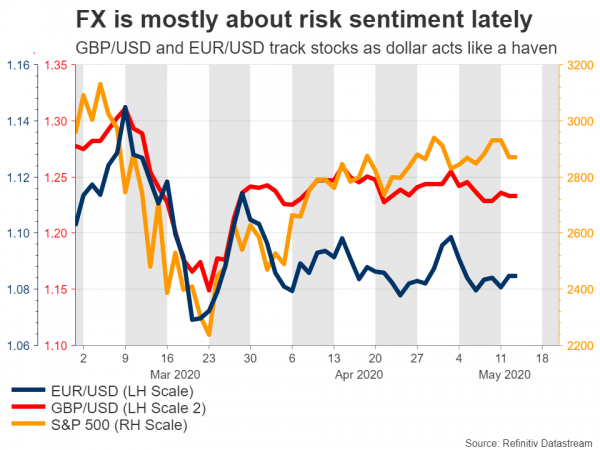

Beyond growth considerations, the other key driver for the currency market will be risk appetite. The dollar has been acting like a safe haven during this crisis, meaning that pairs like euro/dollar and sterling/dollar tend to track stock markets nowadays.

In this sense, the theme that’s likely to dominate ahead of the November US presidential election is the ‘new cold war’ between the US and China. Even before the pandemic, relations between these superpowers were icy cold, but now things have escalated to a whole new level as President Trump pins the blame for the virus outbreak on Beijing.

It’s now clear that Trump’s election strategy is to launch a full political assault on China, so tensions are likely to escalate further heading into November. Whether that will happen via another round of tariffs, via blocking US pension funds from investing in Chinese stocks, or by restricting the access of Chinese companies to American capital markets, remains to be seen.

Staying in the political sphere, the Brexit process will be another hotspot to watch. Negotiations have been slow and fruitless amid the pandemic, but the UK leader has been adamant he won’t request an extension to the transition period that runs out at the end of this year. If he changes his mind, he would need to request an extension by June 30 – otherwise, a no-deal Brexit becomes the default option again.

FX implications – the good and the bad

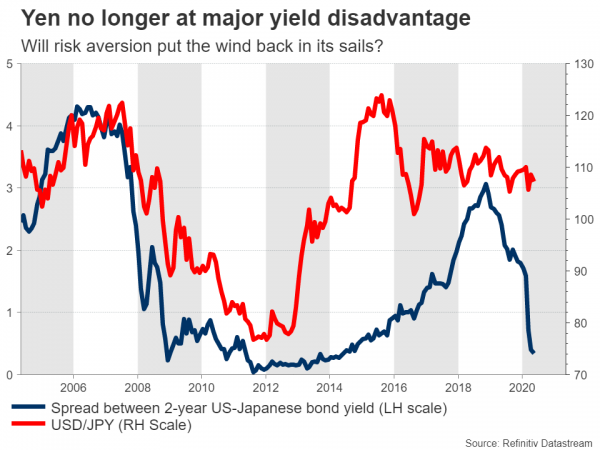

Adding everything up, the yen seems the most attractive in this new FX world, at least for now. First, the fact that rates are now at zero globally probably benefits the yen the most. For many years the Japanese currency suffered from a severe yield disadvantage because the Bank of Japan boasted the most aggressive stimulus program in the world. That handicap has now been nullified to a large degree.

Second, many risks lie on the horizon, and the yen is the leading haven currency. Markets are sanguine for now thanks to a deluge of stimulus and liquidity, but that may not last if second waves of infection hit, or if US-China tensions flare up further, or if the economic recovery is slower than the record comeback currently implied by stock valuations.

The dollar’s defensive qualities have also been on display lately. However, the reserve currency has lost its sizeable yield advantage, and while safe haven flows have prevented it from depreciating so far, that might change if the US is hit by multiple infection waves and is forced into rolling shutdowns. Sadly, that’s a non-negligible risk since America is opening up while new infection numbers are still elevated.

In the commodity currency sphere, it’s a more neutral situation. While Australia and New Zealand have fought off the pandemic better than most, they are export-driven economies, so global developments matter as much, if not more, than domestic ones. Hence, boiling US-China tensions and dwindling global trade could keep a lid on their recovery.

It’s also difficult to have any real confidence in the pound ahead of what promises to be another drama-packed round of Brexit talks. Moreover, the UK is behind most nations in opening up.

But the real casualty could be China’s yuan. Yes, that exchange rate is mostly controlled, but if market forces start pushing it down as Trump becomes more hawkish, there’s only so much that even the mighty Politburo can do. On the other hand, despite the high cost of the trade slowdown, the Chinese domestic economy appears to have the relative advantage of being the first to emerge from the lockdown as it was also the first to be hit by the virus.

Could the devastated euro capitalize on all this? EU infighting and the lack of powerful stimulus have wrecked the single currency, and truth be told, there isn’t much to be optimistic about in the Eurozone. But should the dollar lose ground as a result of second waves, that could set the stage for a mild recovery in the euro from depressed levels, particularly if the EU finally delivers a serious stimulus package. Alas, even in this case, it’s unlikely this will mark the beginning of a long, healthy uptrend in euro crosses, especially euro/dollar.

All told, many challenges remain as economies reopen and a lot will depend on whether second waves hit. What seems more certain though is that geopolitical tensions are set to flare up, making a bad situation even worse.