It’s been a month since I wrote a Perspective outlining a thought-framework on the economic transmission of COVID-19. In fact, it didn’t even have a name then. It’s now worth revisiting that framework with the benefit of some data and hindsight.

Financial markets are sitting at the nexus of peak uncertainty. News is rapidly evolving, literally from one day to the next. In the January Perspective, I made several points that have since been reinforced.

- The SARS experience showed that opaqueness surrounding the spread of the virus and its impact had the potential to worsen in the weeks ahead.

- Check. This has lived up to expectations.

- Markets always fear what they cannot accurately measure.

- Check. The VIX has surged north of the 40-threshold, consistent with the rapid stock market correction of 10 to 12% that occurred in just 5 days.

- Along this vein, we noted to expect bouts of volatility will persist.

- Check. This has a low probability of abating in the very near time until data can confirm successful containment within some of the highly impacted regions. This could then become a signal that the same success can be achieved in North America, imparting a relatively short-lived shock on corporate earnings and the economy.

Also in the January Perspective, three pathways were identified to help monitor the transmission and depth of economic impacts. The first two pathways would be dependent on the success of China and other countries to limit its spread, combined with consideration of the economic reach of the impacted regions. This has evolved into largely a bad news story, with some glimmers of hope.

On the latter, China’s aggressive quarantine measures created a large near-term hit to economic activity. Early reads of February data are confirming a deep, unprecedented downturn. China’s manufacturing PMI went into a free fall, hitting 35.7 in February. This is lower than the financial crisis experience (38.8). But, we hope this will mark the trough. The rapid decline in reported new virus cases is already prompting Chinese authorities to attempt to normalize operations by the end of this quarter. Absent another large breakout elsewhere in the country, we estimate that China’s economy will contract in the first quarter by roughly 2.5% annualized. This would mark a first in the modern history of China’s GDP data.

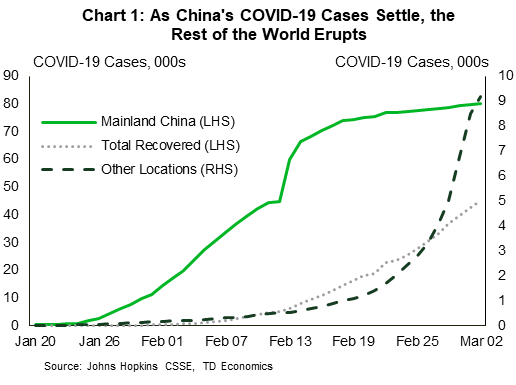

If that’s the ‘good news’, now let’s turn to the bad news. Containment of COVID-19 remains elusive outside of China (Chart 1). There have been significant breakouts in South Korea, Japan, Iran and surrounding regions. The rapid spread of the virus in Italy became the canary in the coal mine for other parts of Europe. And North America is now on high alert, with reports trickling out of an increase in confirmed COVID cases along the western United States. Canada is also seeing the number of confirmed cases tick up within major cities.

Although the number of new cases in North America remain low at this stage, it no longer matters. The fear has set in within financial markets for the potential of global supply chain disruptions. This supply-side shock could morph into a demand shock as fear and quarantine measures unravel household and business confidence.

With the benefit of time to prepare and learn from the Chinese experience, our adjusted baseline forecast assumes countries will succeed in containing impacts to a one-to-two month shock. However, it will be weeks before countries will be able to evidence success on this front.

How have our forecasts migrated?

It’s important to first remind ourselves that the economic impacts are not from the mortality rate of the virus, but rather from strong government and business measures to contain the virus via quarantines and other restrictions, be it mandated or voluntary.

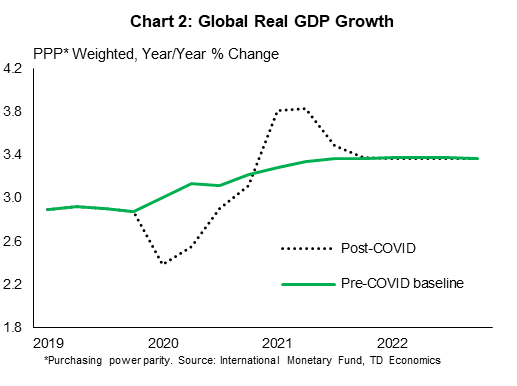

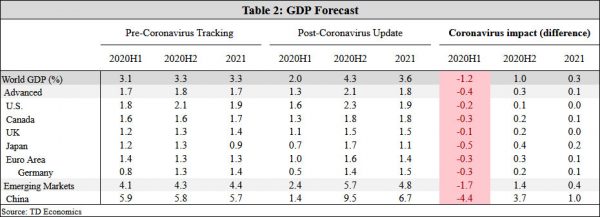

Based on the impacted regions and their mitigating responses to date, the impact on our global growth forecast will be at least 40 basis points lower than our baseline forecast in December. This equates to a 2.7% growth rate. Admittedly, this estimate remains a moving target that assumes economic activity begins to largely normalize within the second quarter and only time will tell (Chart 2).

As for the U.S. and Canada, we have done preliminary estimates by analyzing four main economic channels.

- Tourism and travel

- Supply chains via intermediate exports and imports

- Terms of trade via commodity and currency movements

- Market sentiment via risk premiums

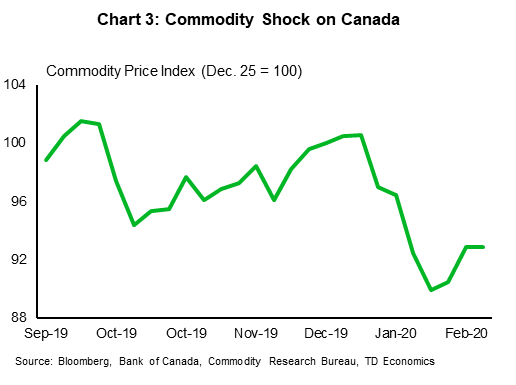

Of the four, assumptions that underpin the latter carry the most significance in our models. It’s also perhaps the least predictable. Unlike the U.S., Canada bears an additional negative weight from the terms of trade shock, marked by plummeting commodity prices and a relatively resilient currency that’s offering little offset (Chart 3). Finally, the travel and supply chain links are lower for the U.S. than they are in Canada as well, largely because Canada is a small, open economy that relies far more on commodities and goods exports relative to its southern neighbor. Putting the pieces together, we have marked down the Canadian forecast in the first quarter by 70 basis points (to 0.8% annualized), and that of the U.S. by 50 basis points (to 1.4%). Given that the adjustment period for both countries is occurring in March, the weak hand-off into the second quarter causes the rebound to be distributed into the following two quarters (Q2 and Q3). However, make no mistake about it, our baseline currently anticipates that both countries will bounce back to life as the virus threat abates over the spring months.

Of the two countries, we have a bit more confidence on the forecast path for the U.S. relative to Canada. The U.S. economy has proven to be the steady-Eddie of the world these days. Real GDP growth has turned in a 2% performance for three straight quarters, sometimes outstripping peer countries by a wide margin. And, excluding the hit from the production shutdown at Boeing, momentum in the first quarter was again looking solid around this mark before the virus came into focus. There are also some big outperformers emerging in the data. Residential investment is clocking in north of 10% in the first quarter, despite consumer spending holding near the 2% mark. The bottom line is that the U.S. was standing on firm ground before the virus shock came into focus. This supports the notion that any economic recovery should parallel historical experiences of being V-shaped.

Canada, on the other hand, is standing on a much thinner growth-cushion, coupled with heightened household financial risks. Of the past five quarters, only one has meaningfully exceeded the one-percent mark for real GDP growth. With GDP per capita languishing, much of the expansion hinges on a heavily-indebted consumer and over-heated housing market. Maintaining household confidence carries far more urgency in Canada, particularly since a low yield environment and a solid labor market have not been a positive enough backdrop to prevent a rise in insolvency rates, particularly in Ontario. As we’ve written ad nauseum in the past, government and central bank policies need to be proactive not reactive, because of the potential for elevated debt levels to ignite an economic tailspin. So, if history comes into play, Canada should mirror a v-shaped rebound in activity as virus-fears abate, but this materially depends on the confidence channel remaining defiant in the face of mounting risks.

Government spending to the rescue?

Given the recent depth and breadth of financial market angst, expectations have become heavily rooted in central banks riding to the rescue by cutting rates. In fact, the market has priced at least three rate cuts by the Bank of Canada and the Federal Reserve over the next twelve months. We don’t agree with this view but understand the market’s logic. In the absence of governments acting proactively, markets turn to the central bank as the only game in town that can respond swiftly, even if the policy action itself may prove to have limited effectiveness.

Monetary policy is generally not highly effective in resolving supply-side shocks. Rather, its first order of business should be to address liquidity strains to prevent the amplification of the financial shock. In contrast, fiscal policy is effective when targeted at the source of the supply shock. However, what we are witnessing today is extremely complex because the global reaction to quarantine and restricted operations risks a strong fear-based response on the demand side. If the disruption is believed to not be temporary or have a ‘contagion’ effect to household sentiment, then monetary policy needs to step in, but only in coordination with fiscal stimulus. It cannot do the heavy lifting and must act as a partner.

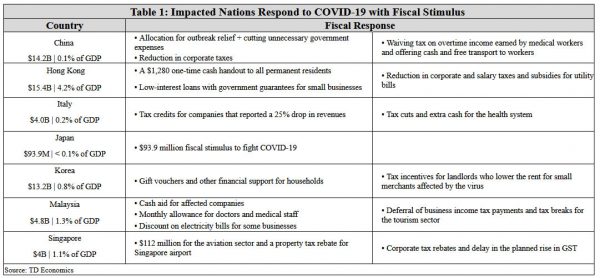

This is exactly what’s already occurring elsewhere. Several governments within virus-impacted countries are moving quickly to announce financial support, largely oriented to the most vulnerable areas of the economy: small businesses, households and the services sector (tourism and transportation in particular). We would expect no less from the U.S. and Canada should the virus materially impact the ability to conduct business or interrupt income for households, particularly those who are reliant on hourly wages. This assumption of fiscal assistance is embedded within our forecast.

Among those countries that are engaging in emergency fiscal stimulus, the amounts vary but some are substantial at 1% or greater as a share of GDP (Table 1). Although U.S. Congressional leaders are drafting an emergency spending bill that would allocate $4-$8 billion to combat the spread of COVID-19, this is not ‘fiscal stimulus’ in the true sense. These are funds necessary to support healthcare operations, supplies and worker preparedness, but are not fiscal stimulus supporting vulnerable businesses and households. In an interesting twist, economists have long noted that government fiscal stimulus should be playing a larger role in supporting the economy relative to monetary policy given the low level of interest rates. This virus is incenting exactly that. The challenge for governments is to act swiftly and decisively to shore up confidence and mitigate negative income impacts. In contrast, the primary focus of the central bank should be to ensure liquidity and credit support should market stresses become apparent.

What if we’re wrong?

Forecasting in the eye of the storm requires a strong dose of humility. The rapid evolution of events creates difficulty in hitting a moving target. As evident from the above statements, forecasters must embed a high degree of subjectivity. Uncertain times like this call for scenario analysis that can at least offer potential upper and lower bound estimates as events evolve.

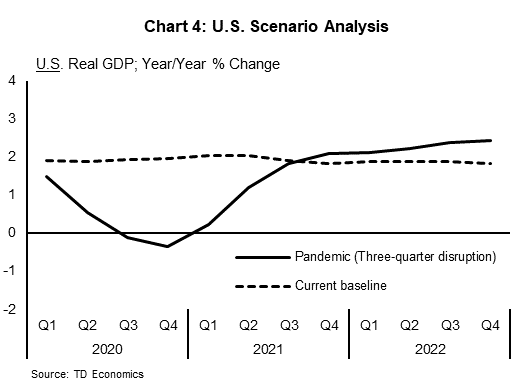

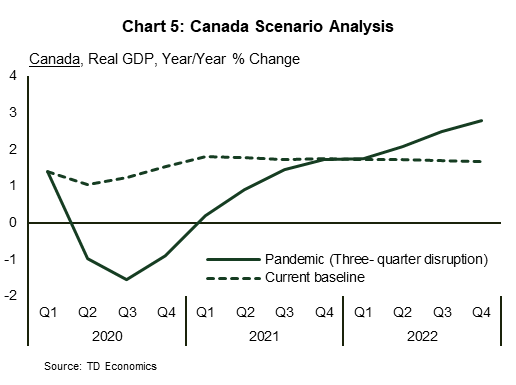

On that front, we’ve laid out two alternative scenarios. The first involves a more entrenched economic weight over a full quarter in North America. This would likely result in a flat economic performance in the U.S. and quite possibly a technical recession in Canada. This scenario is next in line to unseat our current view should there be a larger spread of the virus within major urban centers that forces similar government and corporate responses as seen abroad. The second scenario is a worst-case outcome, reflecting a pandemic with long lasting economic distortions extending three full quarters. This would surely turn into a recession within both the U.S. and Canada, as well as globally (Charts 4 and 5).

In the one-quarter scenario, it’s presumed that firms resist layoffs due to the temporary nature of the economic shock. Hourly wage workers would still impacted due to greater vulnerability of interrupted income opportunities, but salaried employees are largely shielded and maintain a steady income flow. In contrast, the three-quarter pandemic makes this position untenable for employers. Wider scale layoffs would ensue, and unemployment rates would rise by several percentage points in each country.

Canada would be at a clear disadvantage in this scenario, as the shock to heavily indebted households would lead to a more scarred economic landscape. However, both history and the recent experience of China suggest this is a low-probability outcome and is not currently in our line of sight.

Bottom line

Forecasting such a rapidly changing environment is risky business. The near-term forecast will embed wider than usual error, but it’s important not to focus on point estimates and instead pull the lens back. History supports a rebound once the fog of uncertainty lifts. Whether that’s in one month or two months does not change this point. The Federal Reserve and the Bank of Canada stand ready to act and are likely to do so with at least one rate cut should market nerves remain frayed. But, governments need to do the heavy lifting if risk-off behavior within corporate America and Canada causes income disruptions, places the health of small businesses at risk and undermines broader household confidence. In fact, financial markets may draw comfort in knowing that governments have an action plan that can be quickly executed in advance of these disruptions. Transparency could take some pressure off central banks to be thought of as the only game in town that can quickly mobilize.