The Bank of Canada held interest rates unchanged this week, as widely expected, but clearly signalled that a cut could be coming if domestic economic growth numbers continue to disappoint. Near-term external growth concerns have eased with the US-China ‘phase 1’ deal signed and the approval of the USMCA (NAFTA replacement) in Congress. But a run of weak Canadian domestic economic data has nonetheless clearly shifted focus to concerns about the Canada-specific growth backdrop.

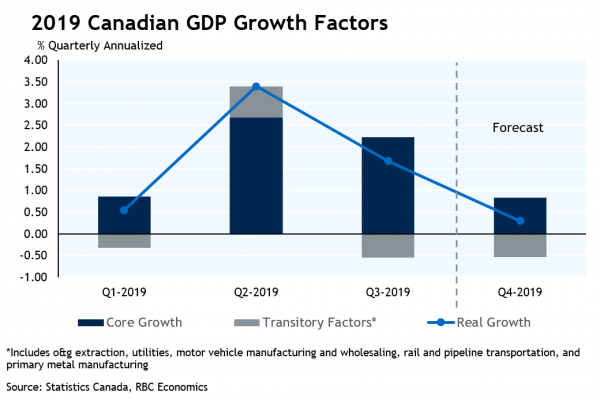

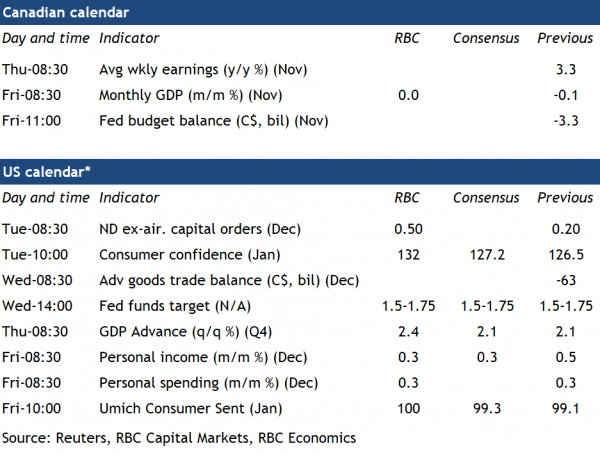

That should serve only to increase attention on the November Canadian GDP report on Friday – and early indicators have been pointing to another soft outcome. Our own tracking is for a flat reading after the already-soft 0.1% decline in October. That would leave the economy on track to grow little if at all in Q4 as a whole (we have pencilled in a 0.3% increase for now). As was the case through most of last year, ‘transitory factors’ – idiosyncratic temporary disruptions in some subindustries that don’t tell us that much about underlying growth momentum – once again will impact the numbers. The CN rail strike in late November will weigh directly on transportation output, and also appears to have been to blame for a large chunk of a pullback in manufacturing sales in the month. Still, not all of the softening in Q4 GDP growth can be so easily dismissed. By our count, even excluding the growing list of industries that have been impacted by significant transitory disruptions in recent quarters, economic growth would be on pace to slow to a sub-1% increase in the fourth quarter.

Of course, Canadian economic data is volatile at the best of times. We saw similar softness in economic data over the winter a year ago only to see a bounce back in the spring. What happens abroad does still matter for Canadian go-forward growth expectations, and that near-term external backdrop still looks a little better in early 2020. The UK will officially leave the European Union next week, but with the status quo relationship remaining in place until at least the end of 2020. Persistently resilient labour market data and a bounce-back in survey economic indicators (the December PMIs) were strong enough that the Bank of England is likely to stay on the side-lines and face Brexit with interest rates where they are for now. More importantly for Canada, the US industrial sector has shown signs of perking up despite tariffs on China still in place. In contrast to Canada, US GDP growth looks like it picked up in Q4 to close to a 2½% rate and there is little to point to a significant deceleration early in 2020. At least some of that strength will benefit Canada as well, just as weakness in the US economy a year ago ultimately spilled north of the border. We continue to think that Canadian economic growth data will bounce-back somewhat over the first half of 2020 – but not significantly enough to keep the BoC from cutting rates in April.