With the final touches being put to the phase one US China trade agreement, markets have been quick to focus on the potential disruption that such a sizeable agreement might have on existing trade flows. This brief note takes a top down look at the potential for China to actually be able to buy as much as $50bn of energy exports from the US, and the potential implications on other exporters in the region.

Will China be able and willing to buy US$50bn of US energy products?

With the final touches being put to the phase one US China trade agreement, markets have been quick to focus on the potential disruption that such a sizeable agreement might have on existing trade flows. To date, much of the focus has been on the potential impact on agricultural markets.

However, a number of news sources have suggested that “the target for manufactured goods purchases will be the largest, worth around $75 billion. China will also promise to buy $50 billion worth of energy, $40 billion in agriculture and $35 billion to $40 billion in services” (Source Politico.com).

While we await full details of the US China phase one trade deal, this brief note focusses on the potential for China to be able to buy $50bn of energy exports from the US, and the potential disruption that this might mean for the likes of Australia, as an existing significant thermal energy exporter in Asia.

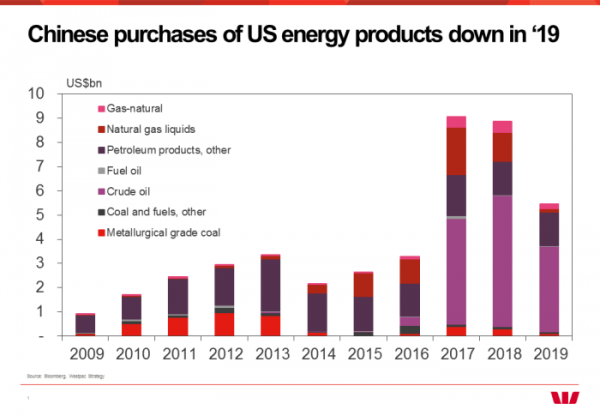

The first obvious point to note is that if China has indeed “promised to buy $50 billion worth of US energy” over a 2yr period, then this would mean that the next two years will need to see circa double the previous back to back record purchases of US energy products. Using US Census Bureau data, the best years for US exports of energy to China were 2017 and 2018 (circa US$9bn in each) and purchases in 2019 have been well down from those records (circa US$5.5bn).

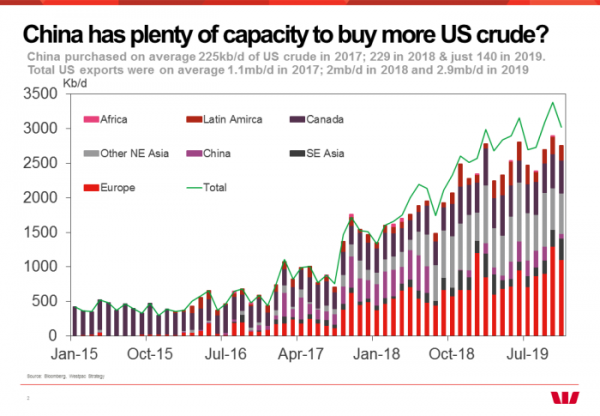

This sharp drop in energy purchases in 2019 versus strong purchases in 2017/18 would suggest that China has plenty of capacity to increase imports of US crude – at least to the extent that Chinese refineries can handle the increasingly light/ sweet US crude output that is.

China purchased an average of 225kb/d of US crude in 2017; 229kb/d in 2018 but just 140kb/d in 2019. Total US exports were on average 1.1mb/d in 2017; 2mb/d in 2018 and 2.9mb/d in 2019. So at the same time that US crude exports increased by a factor of close to 3, Chinese imports have almost halved suggesting plenty of upside.

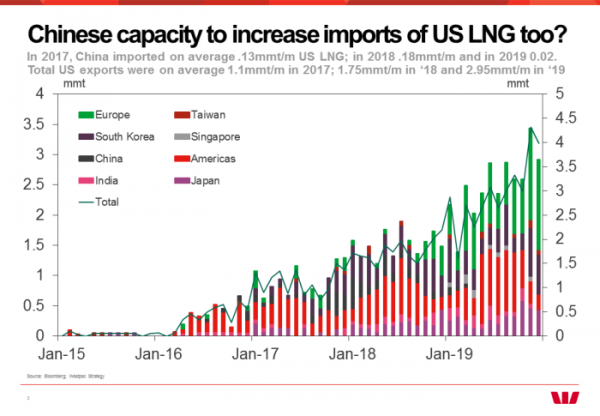

The above argument would then suggest that China also has capacity to increase purchases of LNG from the US. In 2017, China imported on average 0.13mmt/m of US LNG in 2017; in 2018 0.18mmt/m and a tiny 0.02 mmt/m in 2019 (and zero between April 2019 and Dec 2019).

Total US LNG exports were on average 1.1mmt/m in 2017; 1.75mmt/m in 2018 and 2.95mmt/m in 2019. So at the same time that US exports of LNG have almost tripled, Chinese imports from the US have effectively dropped to zero again suggesting significant potential for additional purchases.

Now were China to significantly increase LNG purchases from the US, this could be a potential risk for Australia given the importance of China as an export destination. Of the 76mt of LNG that Australia exported in 2019, 40% went to Japan and 37% went to China.

However, we would tend to downplay the risks for 3 reasons.

However, we would tend to downplay the risks for 3 reasons.

Firstly, the bulk of Australian exports would tend to be on fixed long term supply contracts.

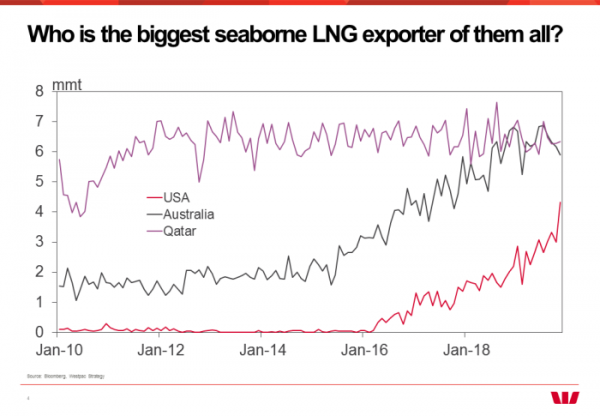

Secondly, US exports have been increasingly consumed by Europe. In the last year, 30% of US LNG exports were imported by the Europe (and just 15% by South Korea and 10% by Japan) emphasising that there does not appear a lot of capacity – at least in the short term – for the US to divert current exports away from existing LNG trading partners to China.

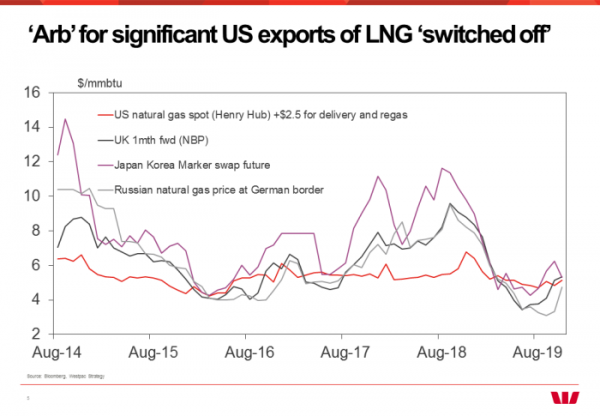

The third reason we would note here is on the economics of US LNG exports to Asia. Prices of LNG around the world are so weak (due to a glut of LNG in Asia) that the ‘arb’ for US exports has effectively been switched off. This can be seen in the chart above. If we assume a fixed US2.50 for US liquifaction, transport and regasification then additional US exports barely make sense at the moment suggesting it is not efficient for the US to ramp up exports of LNG into China.

The third reason we would note here is on the economics of US LNG exports to Asia. Prices of LNG around the world are so weak (due to a glut of LNG in Asia) that the ‘arb’ for US exports has effectively been switched off. This can be seen in the chart above. If we assume a fixed US2.50 for US liquifaction, transport and regasification then additional US exports barely make sense at the moment suggesting it is not efficient for the US to ramp up exports of LNG into China.

Now as above, we await the finer details of the US China phase one trade agreement with great excitement. However, if newswires are correct and China has committed to vast purchases of manufactured goods, energy, agriculture and services; if there is a monitoring and compliance framework which ‘forces’ China to meet these purchases and if China’s “increased imports of U.S. goods and services are expected to continue on this same trajectory for several years after 2021” as USTR factsheet suggested, then this could have a material impact on energy supply chains in the region.

While we fully acknowledge that China has the capacity to significantly increase US energy purchases, we are sceptical that China will be able to buy that much energy from the US, and that the US will be able to economically supply that much energy to China. We thus await full details with great interest.