Highlights

- Global export growth has flatlined of late, and Canada has not been immune. A slower pace of global growth and U.S. bilateral efforts suggest that the struggle is likely to continue.

- There is room for cautious optimism. Canada’s past success on securing multi-lateral trade agreements (CETA and CP-TPP) have positioned it well to preserve market share gains as well as offered a head-start to exporters.

- Despite the U.S. favouring more narrowly defined bilateral agreements, multilateral arrangements are still the order of the day globally. New and deeper trade opportunities still exist for Canadian (and global) exporters.

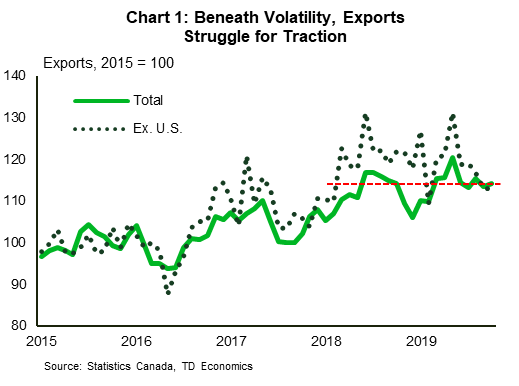

Canadian exports have struggled to gain traction over recent years (Chart 1). Soft global growth and elevated trade policy uncertainty are the culprits. But over this time, Canada has made marked advances in pursuing and ratifying multilateral trade agreements, as have other advanced economies. As this report will argue, these agreements position Canadian exporters well even as the U.S. pursues competing bilateral agreements around specific sectors (usually agriculture, motor vehicles, and energy). This can be seen in the relationship with Japan. CP-TPP has given Canada a ‘head start’ on building relationships and market share. Similarly, the agreement with the European Union protected Canadian beef quotas, leaving other countries paying the price for a deal struck in early August that increased U.S. market access for this product.

No discussion of international trade is complete without mentioning the elephant in the room. The U.S. continues to ratchet up pressure on many of its trading partners. Recent developments have seen a continuation of this strategy, with questions surrounding the timing of a ‘phase one’ U.S.-China trade deal, while new tariffs were announced/threatened on Brazil, Argentina and France within a single week. Despite this, other economies continue to move forward on multilateral trade deals, showing that beneath the fog of uncertainty, opportunities still exist.

Canada Back to ‘Only’ TPP Advantage in Japan, but with a Lead

What began life as the Trans-Pacific Partnership became the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CP-TPP). In the process, this ‘next generation’ trade deal lost the participation of the United States and some of its demands, notably around dispute settlement and copyright lengths. Ultimately, 11 countries signed on, representing more than $10 trillion in combined GDP.1 Trade agreements often take time to bear fruit, and CP-TPP has only been binding for less than a year (from December 30, 2018). But, there have already been some encouraging signs. For example, exports of beef and related products to Japan were up more than 67% year-to-date through September, more than triple the growth in shipments to other destinations. Canadian exporters now get the same terms as many of the international competitors. Canadian producers (and other signatories) will see beef tariffs fall to roughly a quarter of their pre-agreement level over the next decade or so.

Japan also presents an interesting ‘challenge’. While the U.S. is not part of CP-TPP, a bilateral agreement between the world’s largest and third-largest economies was recently agreed. What does this mean for Canada? A few key points bear noting: first, for several agricultural products, the U.S. will be “catching up” to Canada, notably for beef and pork, and also wheat and corn. U.S. products in these categories will face similar reductions in tariffs as Canadian products starting from January 2020.2 The distinction is that Canada has had more than a year’s lead-time to establish supply chain connections, branding, etc. Second, as noted, the bilateral agreement brings the U.S. to where it would have been under the original TPP for these products – so Canadian producers still have greater market access than would otherwise have been the case.3

Finally, it is important to remember that the U.S. bilateral deal isn’t a full trade agreement. While there are some modern aspects to it, such as provisions around online content purchases, many key areas of trade such as autos, aircraft, semiconductors/electronics, etc. are not covered in this initial bilateral deal. Some of these areas were left for later negotiations in 2020 and, potentially, beyond. More than this, the “bi-” part of the deal is important. Canada has barrier-free access to supply chains throughout CP-TPP signatories (i.e. Canadian lumber used in a Japanese product shipped to another CP-TPP signatory). This is a rules-of-origin benefit that the U.S. does not have. Canada also benefits from mutual recognition of credentials, easing border crossings for work, and enhanced provisions around services, including categories where we tend to punch above our weight, such as insurance. In short, the U.S. has caught up as a supplier to Japan in some specific product categories with their bilateral deal, but Canada maintains the benefit of a multilateral framework that offers the advantage of more product export breadth and more market access across countries. Compared to the pre-TPP world of five years ago, Canada is definitely better positioned now.

CETA Helps Canada Avoid EU Quota Changes

Remember the old Facebook status option “It’s Complicated”? That statement best describes the interaction between European trade and agriculture policies, U.S negotiations, and market access under the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). In terms of U.S. manoeuvres to date, its again all about agriculture. In early August, the EU and U.S. agreed to a deal on beef. How does this impact Canada? Thanks to CETA, very little. Under CETA, the Canadian beef quota will rise by about 46k tonnes by 2022, to reach 68k tonnes. About 4.2k of this gain came from a ‘shared’ quota of 45k tonnes. This is a legacy of a hormone-free beef import quota that was initially introduced in 2009 to settle a dispute with the U.S. over the banning of growth hormones in the EU. In doing so, the quota was made available to other countries in order to be WTO compliant. It is this ‘shared’ quota that is affected by the bilateral U.S.-EU agreement: 35k (or about 80%) of it will be allocated to U.S. producers after seven years (from 18.5k initially). Before this, other producers, notably Australia and Uruguay, had steadily taken up quota share, leaving the U.S. with about 30% of the total. It is these countries, as well as Argentina, that stand to lose from the U.S. agreement. Indeed, depending on how existing quota shares are divvied up, this means Canada’s quota would, at the maximum, rise by ‘only’ 42k tonnes – still roughly a tripling in size relative to pre-CETA shares.

In this case, CETA acts as a ‘shield’ of sorts. And, much like the situation described with CP-TPP and the U.S.-Japan bilateral deal, CETA is in a different class from a single-product trade deal, covering many more product categories as well as services, government procurement, and so on, as a modern trade deal. Once again, Canada’s position within a relatively complete trade framework helps moderate the influence of competitive bilateral/limited coverage agreements emanating from the U.S.

U.S. Behaviour the Wildcard

As far as Canada’s existing trading relationships and agreements go, there is clearly some reason for cautious optimism, except for the elephant in the room: trade with China and the scope for a cooling of U.S.-China trade tensions. On the bilateral relationship, China recently lifted its ban on Canadian pork products – unquestionably a positive development. But, we caution against too much exuberance as the decision was likely related to domestic challenges owing to the loss of livestock from swine disease, rather than signalling a broader détente in tensions. Many Canadian agricultural and other producers remain effectively shut out of the Chinese market. As of November, Canadian exports to China were down nearly 10% from their January 2019 high.

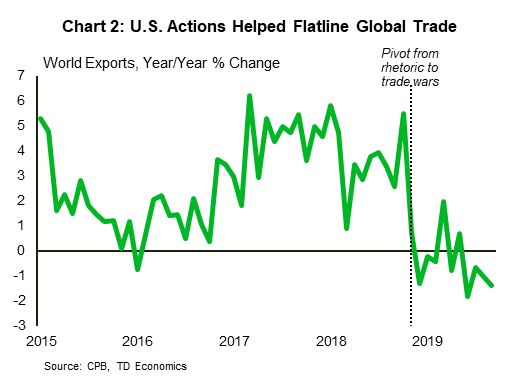

Past TD Economics research found little scope for Canadian firms to benefit from trade diversion or other potential opportunities that could flow from China-U.S. trade obstacles. Rather, the elevated uncertainty has joined other factors, such as slowing Chinese demand, in sending global trade volumes lower (Chart 2). Integrated global supply chains and the necessity of rules-based interactions are unable to avoid uncertainty shocks, even if they stem from bilateral relationships, such as U.S.-China.4 It isn’t just trade either, but business investment as well, even in the United States. With the timing and scope of any U.S.-China deal uncertain, and taking the already mentioned threats and promises of further tariff actions against other partner into consideration, trade uncertainty seems unlikely to dissipate any time soon.

It’s Not Us, It’s You

In the interest of not ending on a sour note, lets pull the lens back from the U.S. for a moment. Other global nations have not bought into the notion that bilateral trade deals are the best option. Around the time that President Trump took office, investor fears seemed to mount that protectionism would become the name of the game and the global trading environment would see a marked shift away from the multilateralism that defined the past few decades. However, the U.S. has by and large gone it alone on that front. We’ve already discussed Canada’s key agreements, but we haven’t been alone in maintaining a multilateral approach to trade discussions. Fifty-four African Union nations are now inside the African Continental Free Trade Area. And there has been significant progress on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). This agreement covers 15 Pacific countries representing a quarter of global GDP, including Australia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, and South Korea. Early reports suggest that the agreement could come into effect as soon as next year. While not as comprehensive an agreement as CP-TPP or others, RCEP nevertheless provides concrete evidence that major advanced economies (including large ones) continue to see value in multilateral frameworks. The U.S. stands alone in its decision to pursue bilateral agreements that have, so far, been limited in scope.

Bottom Line

There is no denying that Canadian exports have had a rough go of it lately. But, there are some reasons for cautious optimism. It is only early days for both CETA and CP-TPP, and in both cases Canadian firms have been given an advantage in market access vs U.S. (and other) competitors, even if it won’t last forever. Capitalizing on this advantage to build out or expand trading relationships and supply chains can support export growth going forward. Why cautious optimism? U.S. trade policy is maintaining maximum uncertainty within the global environment, particularly through the active and frequent use of tariffs. This frays the sentiment channel and holds back global investment and trade volumes even among those not directly impacted. So, unless there is a marked change in U.S. trade policy (as we don’t believe there will be), exporters will have to navigate a fog of uncertainty to realize the gains from new and expanded global opportunities.

End Notes

- The countries are: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam.

- The enabling legislation passed on December 4th.

- It bears noting that major agricultural associations were generally supportive of TPP at the time of negotiation.

- Or U.S.-France, or U.S.-EU, etc.