Executive Summary

- Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party is projected to win a majority in Parliament at next week’s U.K. general election—this is our base case scenario.

- In this scenario, U.K. Parliament would likely ratify the withdrawal agreement and the U.K. would leave the E.U. with a deal in place, providing some safeguard against the most economically damaging Brexit scenarios.

- However, a Conservative majority is far from guaranteed. If Conservatives do not secure a majority, the Bank of England may cut rates as early as December amid uncertainty over next steps, which could involve a second referendum, although a “no-deal” Brexit is also still possible in this scenario.

U.K. Prepares for Third Election in Four Years

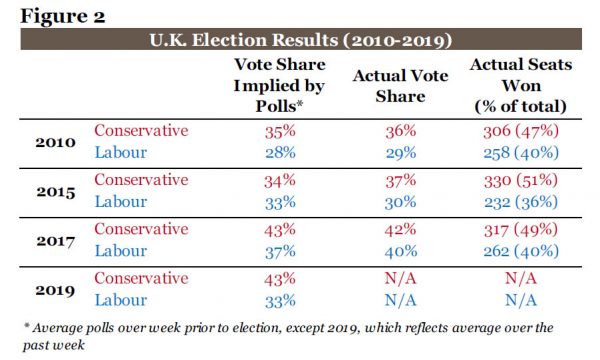

With a week to go until the United Kingdom’s highly anticipated general election on December 12, we take a closer look at the election and the possible implications. First, we remind our readers that this will be a general election in which each of the 650 constituencies across the U.K. will elect a Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons. The leader of the party that wins the most votes typically becomes the prime minister. Voting is conducted on a first-past-the-post basis, such that candidates simply need a plurality of the votes in a constituency to win the seat rather than an outright 50% majority. Accordingly, a candidate can win a seat with less than 50% of the vote, which implies that the share of the vote won by each political party in aggregate may not map directly to the share of seats each party wins in Parliament. For example, in 2015, Conservatives won just 37% of the national vote but secured 51% of seats in Parliament.

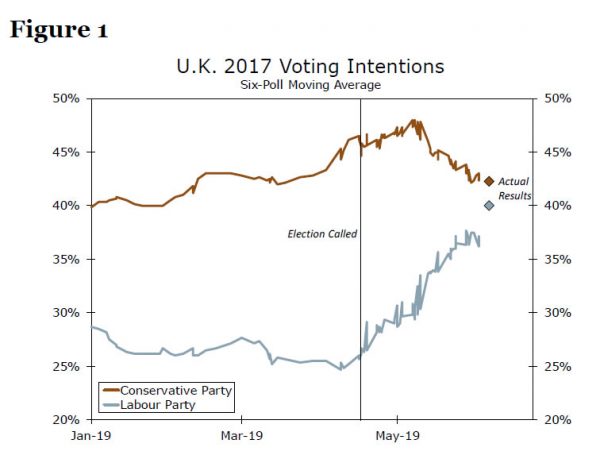

This system adds another layer of complexity and uncertainty to the prediction of U.K. election. We have to contend with uncertainty over not only the accuracy of the polls but also how the actual results will translate into the number of seats in Parliament for each party. As another caveat, we note that we are still a week away from the actual election, and as the 2017 election showed us, polls can shift abruptly in a short period of time ahead of elections (Figure 1).

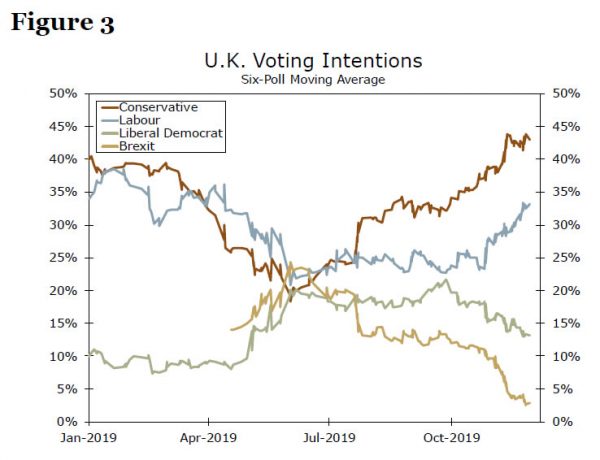

With all those caveats in mind, let us move on to a discussion of where things stand in the current race. Based on the average of all polls over the past week, Conservatives are currently polling at around 43% of the vote, while Labour is in a fairly distant second place with 33% of the vote. As the following table shows, the Conservatives currently enjoy a larger lead in the polls compared to the polls ahead of the past few elections, and importantly compared to the 2017 election, when they surprisingly lost their parliamentary majority. Still, Labour’s support in the polls has been edging higher in recent days, and could continue to do so over the next week or so.

With these polling numbers in mind, let us examine the possible ramifications for the Brexit process and the pound in various election scenarios, starting with our base case: a majority in Parliament for the Conservative Party.

Johnson Still in Poll Position

The most likely outcome based on current polling, and current markets pricing, is one in which the Conservative Party secures a majority in U.K. Parliament and Boris Johnson remains the prime minister. There are few if any certainties when it comes to the Brexit process, but we can say with a substantial degree of confidence that if the Conservatives win an outright majority in Parliament, they will likely ratify the withdrawal agreement and leave the European Union with a deal by January 31, 2020. This outcome, which is also our base case scenario, would provide some safeguard against the most economically damaging Brexit scenarios and would allow the U.K. to finally leave the E.U. with a deal in place.

That said, as we have noted in past reports, this would not mark the end of the Brexit process, but instead the beginning of “phase two,” or longer-term E.U.-U.K. trade talks. During this next phase, the two sides will need to agree on their objectives in longer-term trade negotiations, conduct those negotiations, reach a new trade deal and ratify that deal. However, the current withdrawal agreement provides for a “transition period” of only 11 months (through December 2020) for all of this to occur. It seems extremely unlikely that 11 months is enough time to conclude that process, and thus the two sides will likely have to extend the deadline even further, something hardline Brexiteers may be hesitant to do. Uncertainty over the extension of the transition period could be a downside risk for the U.K. economy if the E.U. and U.K. have not reached a longer term trading arrangement by the end of 2020.1 In the end, however, we expect the two sides to extend deadlines as long as is needed to conduct trade talks.

I’m Referring to a Referendum of Course

What if the Conservatives fall short of a majority in Parliament? We see a considerable chance the Bank of England could cut rates as early as December if the Conservatives do not win an outright majority.

The next steps for the Brexit process in this scenario depend entirely on the election results and the composition of whatever new government is formed. If the Conservatives form a minority government, or are forced to govern in coalition with other parties, one possible outcome would be to call for a referendum on the withdrawal agreement. This referendum would likely ask voters whether they want to leave the E.U. with the withdrawal agreement in its current form or to remain in the E.U. (i.e., cancel Brexit). Importantly, this would not be a re-run of the 2016 “in or out” referendum on E.U. membership, but a new question entirely.

The aforementioned referendum scenario could be quite positive for the U.K. economy, particularly if the end result is to cancel Brexit entirely. However, as noted above, it is highly unclear whether a Conservative minority or coalition government would in fact choose to hold a referendum in the first place. It is entirely possible that the government might have no strategy at all and would simply seek an extension of the January 31 Brexit deadline without a clear strategy for how to proceed, which would lead to a re-emergence of “no deal” concerns. Finally, even if a referendum were called, there would be weeks of uncertainty leading to the vote, and if voters opted for the “leave with a deal” option, the government would be entering E.U.-U.K. trade talks with no Parliamentary majority, limiting its ability to negotiate effectively.

Another possible electoral outcome is a coalition government led by Labour, which could occur if Labour wins the most seats in Parliament, or if it is given a chance to form a government if the Conservatives are unable to do so. Per its election manifesto, Labour’s Brexit strategy would be to renegotiate the Brexit deal with the E.U. and hold a referendum asking voters whether they want to leave the E.U. with this new deal in place or remain in the E.U. (similar to the strategy laid out above, but with a renegotiated deal). If granted the opportunity to renegotiate the Brexit deal, Labour would likely seek a deal that keeps the U.K. in the E.U. customs union, allowing for tariff-free goods trade, although that would almost certainly require closer adherence to E.U. regulations and laws. In short, Labour’s vision for Brexit much more closely resembles the U.K.’s current relationship with the E.U. than the Conservatives’ vision for Brexit. Still, a renegotiation of the Brexit deal along the lines of Labour’s vision may not be possible, and in any case is likely to drag on for several months.

As a final note, and to re-emphasize a point, a “no deal” Brexit is still possible. If the Conservatives fall short of a majority in the election, we see a risk that a minority or coalition government could face the same disagreements as the current government, and could stumble toward the January 31 deadline with no plan for how to proceed with the Brexit process.

As usual with the Brexit process, there are seemingly endless permutations for how things could play out from here. We leave our readers with a few thoughts:

- If Conservatives win a majority, Parliament will likely pass the withdrawal agreement and the E.U. and U.K. will move on to longer-term trade talks.

- If Conservatives do not win a majority, a second referendum is a very real possibility, although this would likely be asking voters some version of “do you want to leave the E.U. with a deal or not leave the E.U. at all?”

- The Bank of England could cut rates as early as December in any scenario other than a Conservative majority.

- Finally, a “no deal” Brexit is still a possible outcome.

1 If the U.K. and E.U. got to the end of the transition period without a trade deal and did not extend the transition, this outcome would be akin to a “no deal” Brexit, but not exactly the same. The main differences are that there would be agreements on citizens’ rights, U.K. payments into the E.U. budget and a mechanism for avoiding a hard Irish border, but it could still end with the E.U. and U.K. trading on WTO terms with significant tariff and non-tariff barriers.