As the global economy has decelerated over the past year, the weakness has been concentrated in the factory sector. In this report, we examine which advanced economies are most exposed to a manufacturing slowdown.

Europe, Japan Exposed to Prolonged Manufacturing Weakness

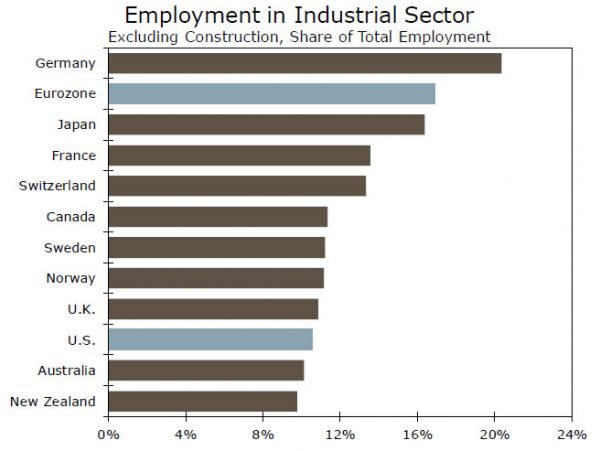

The deceleration in the global economy this year has been marked by pronounced weakness in manufacturing. In the United States at least, it is often said that the U.S. economy can withstand such a slowdown because manufacturing is a relatively small piece of the total economy. According to OECD data on industry ex-construction (which includes manufacturing, mining and utilities), industrial employment in the United States is about 10.6% of total employment. As a share of total U.S. output, industrial production is about 13%.

How does this stack up against the rest of the world? The top chart shows employment in industry as a share of total employment for several key developed market economies. As can be seen, New Zealand, Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom are a few of the countries with the least exposure to industrial labor markets. Conversely, employment in industry is about 17% of total employment in the Eurozone, and for some European industrial powerhouses it is even higher. Just over one in five German workers is employed in the industrial sector. Japan also has a relatively high share of workers employed in industry at roughly 16%.

Thus, it appears that if a sharp contraction in the manufacturing sector were to cause a recession somewhere, the Eurozone may be the first domino to fall, at least among these economies. Given that a larger share of Europeans are employed in the industrial sector, such a slowdown could pose a bigger threat to consumer spending than it would somewhere else, like the United States.

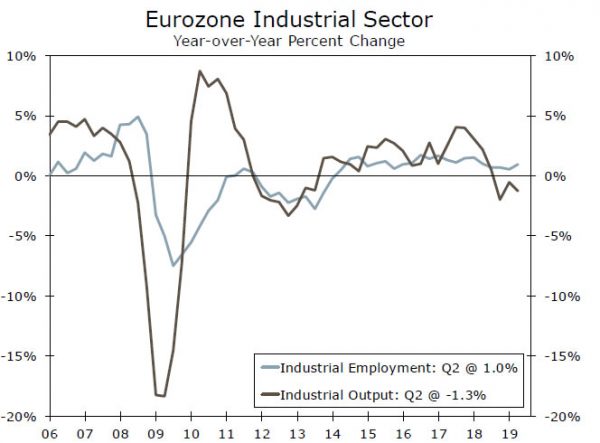

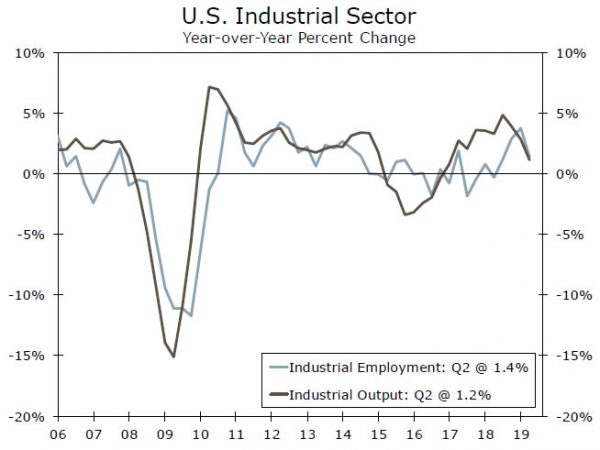

Interestingly, compared to the United States, European industrial employment appears less tightly correlated with Eurozone industrial output. In the United States, the two move mostly in-line with each other (correlation coefficient of 0.77, middle chart). In Europe, however, industrial employment appears less sensitive to declines in total output, at least at first (correlation coefficient of 0.39, bottom chart). This makes some sense to us, as European labor markets are generally considered to be less flexible than the U.S. labor market. A two-quarter lag helps improve the fit for both the U.S. and Europe, though much more for the Europeans. Thus, the longer the manufacturing contraction goes on, the more European job losses might begin to mount.

A more sophisticated statistical analysis suggests that the year-over-year contraction in quarterly industrial value added would have to be about 4-5% to pull the Eurozone economy into a recession, all else equal.1 Industrial output in Europe is not yet declining at that pace (bottom chart), but if the current global manufacturing slowdown continues to worsen, it could push the European economy to the brink.